The Science of Sunsets

October 2024

Everyone at one time or

another has marveled at a strikingly colored sunrise or sunset. Colorful sunrises and sunsets have, in fact,

inspired imagination for centuries. Although

brilliant low-sun colors can appear everywhere, some parts of the world are

especially known for their twilight hues; the deserts and tropical oceans

quickly come to mind. For example,

rarely does an issue of Arizona Highways not include an eye-catching

sunset image; sunsets also often provide the backdrop for Caribbean and

Hawaiian postcard views. Likewise, even

casual observation reveals that colorful sunrises and sunsets favor certain

seasons. For example, in the mid-latitudes,

including much of North America and Europe, fall and winter most often produce spectacular

low-sun hues.

Why do striking sunsets

appear in some parts of the world more than others, and why are they most often

seen during certain months? What atmospheric

conditions create truly memorable sunrises and sunsets? These and other twilight phenomena are

explored in the paragraphs that follow.

What dust and pollution

don't do

It is often stated that

natural and anthropogenic dust and pollution cause colorful sunrises and

sunsets. In fact, the brilliant twilight

"afterglows" that follow major volcanic eruptions do owe their

existence to the injection of small particles high into the upper atmosphere (will

be said on this later). If, however, it were strictly true that an abundance of atmospheric

aerosols, especially in the lower part of the atmosphere, were responsible for

brilliant sunsets, large urban areas would be celebrated for their twilight

hues. In fact, aerosols of all kinds ---

when present in abundance in the lower troposphere as they often are over urban

and continental regions --- do not

enhance sky colors --- they subdue them.

Relatively clean air in the

lower levels is, in fact, the primary ingredient common to brightly colored

sunrises and sunsets.

To understand why this is

so, one need only recall how typical sky colors are produced. The familiar blue of the daytime sky is the

result of the selective scattering of sunlight by air molecules. Scattering is the re-direction of light

by small particles. Such scattering by

dust or by water droplets is responsible for the shafts of light (“crepuscular

rays”) that appear when the sun partly illuminates

a smoky room or misty forest --- or is partly blocked by clouds (Figure 1). Selective scattering, meanwhile, is used to describe

scattering that varies with the wavelength of the incident light.[1]

Particles are good selective scatterers

when they are very small compared to the wavelength of the light.

Ordinary sunlight is

composed of a spectrum of colors that grade from violets and blues at one end

to oranges and reds on the other. The

wavelengths in this spectrum range from .47 um for violet to .64 um for red.

Air molecules are much smaller than this --- about a thousand times smaller. Thus, air is a good selective scatterer. But because air molecules are slightly closer

in size to the wavelength of violet light than to that of red light, pure air

scatters violet light three to four times more effectively than it does the

longer wavelengths. In fact, were it not

for the fact that human eyes are more sensitive to

blue light than to violet, the clear daytime sky would appear violet instead of

blue!

At sunrise or sunset,

sunlight takes a much longer path through the atmosphere than during the middle

part of the day. Because this lengthened

path results in an increased amount of violet and blue light being scattered

out of the beam by the nearly infinite number of scattering "events"

that occur along the way (a process collectively known as multiple

scattering), the light that reaches an observer at the surface early or

late in the day is noticeably reddened.

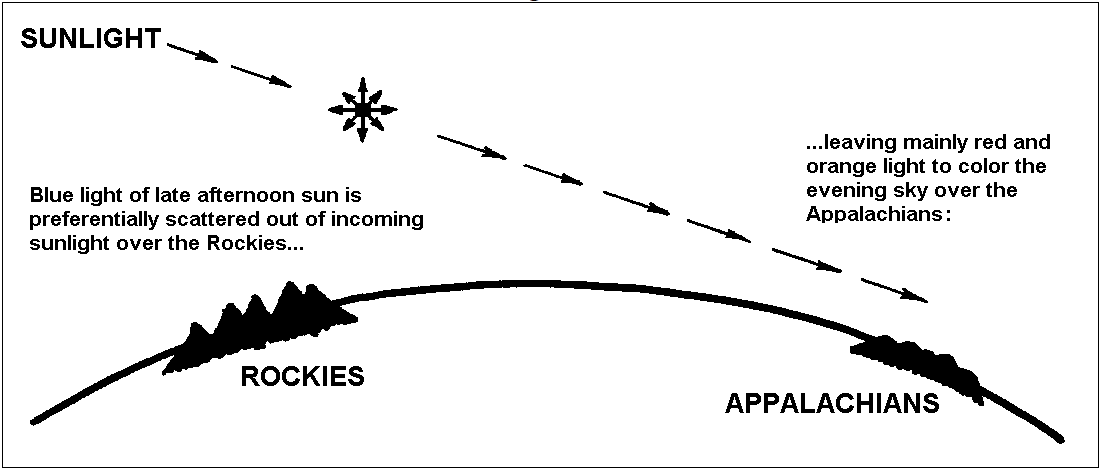

The effect just described

is demonstrated vividly in Figure 1. In

the image, the anvil cloud of an approaching evening thunderstorm is blocking

low-level sunlight and casting crepuscular rays over the middle and right parts

of the view, while unblocked sunlight continues to illuminate the entire depth

of the atmosphere at the left. As the

lower left part of the scene is dominated by sunlight that has taken a long

path through the lower troposphere, that part of the sky appears notably orange

and red. In contrast, in the shadow of

the cloud, where the sky is viewed primarily by scattering from less-reddened

sunlight topping the cloud, the sky is comparatively blue.

Figure 1

Because of the substantial

difference in the path length of sunlight between midday and sunrise or sunset,

it can be said that sunrises and sunsets are red because the daytime sky is

blue. This notion is perhaps best

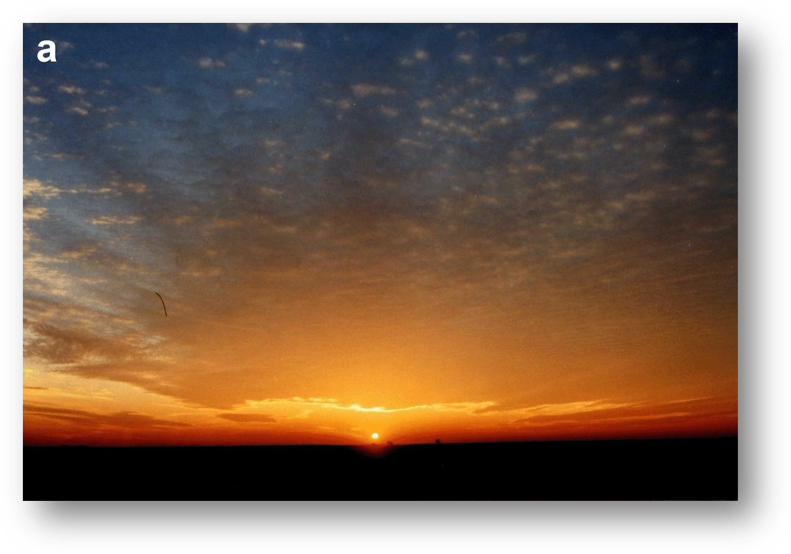

illustrated diagrammatically: A beam of sunlight that at a given moment helps

produce a red sunset over the Appalachians at the same time contributes to the

deep blue of the late afternoon sky over the Rockies (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Now what happens when

airborne dust and haze enter the view? Typical

pollution droplets such as those found in urban smog or summertime haze are on

the order of .5 to 1 um in diameter. Particles

this large are not good selective scatterers as they are comparable in size to

the wavelength of visible light. If the

particles are of uniform size, they might impart a reddish or bluish cast to

the sky or result in an odd-colored sun or moon; it is this effect that

accounts for the infrequent observation of "blue suns" or "blue

moons" near erupting volcanoes. Because

pollution aerosols normally exist in a wide range of sizes, however, the

overall scattering they produce is not strongly wavelength-dependent[2].

As a result, hazy daytime skies, instead

of being bright blue, appear bluish-gray or even white. Similarly, the vibrant oranges and reds of

"clean" sunsets give way to pale yellows and pinks when dust and haze

fill the air.

But airborne pollutants do

more than soften sky colors. They also enhance the attenuation of both

direct and scattered light, especially when the sun is low in the sky. This reduces the total amount of light that

reaches the ground, robbing sunrises and sunsets of brilliance and intensity. Thus, twilight colors at the surface on dusty

or hazy days tend to be muted and subdued, even though purer oranges and reds

persist in the cleaner air aloft. This

effect is most noticeable when viewed from an airplane, shortly after take-off

on a hazy evening. A seemingly bland

sunset at the ground gives way to vivid color aloft as soon as the plane

ascends beyond the hazy boundary layer[3].

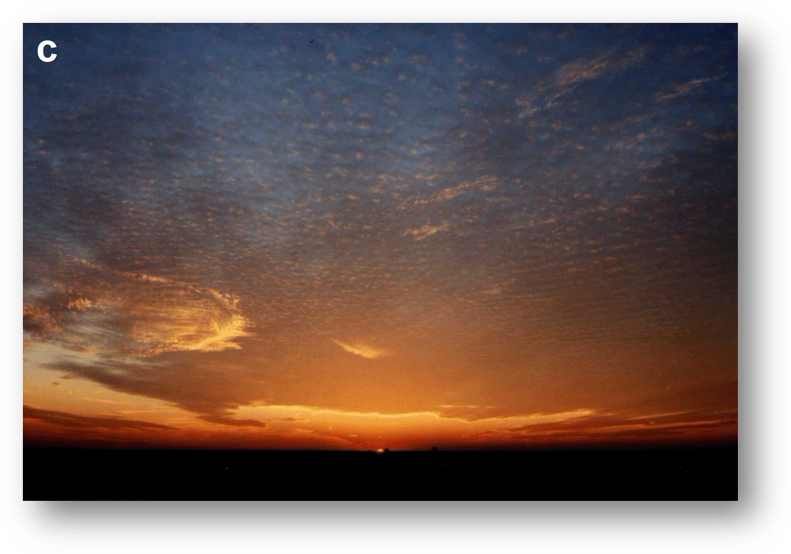

When the haze layer is shallow, a

similar effect sometimes is evident at the surface, as shown by the extended sunset

sequence in Figure 3. The photographs

show a billowed altocumulus wave-cloud formation in the lee of Virginia’s Blue

Ridge Mountains that erupts into a blaze of fiery oranges and reds once the sun

has dropped far enough below the horizon that it no longer directly illuminates

the thin veil of haze present below the clouds. The haze layer appears as a dark band just

above the horizon in the last (enlarged) view.

Figure 3

Because air circulation is

more sluggish during the summer, and because the photochemical reactions that

result in the formation of smog and haze proceed most rapidly at that time of

the year, late fall and winter are the most favored times for sunrise and

sunset viewing in most parts of the world. Pollution climatology also largely explains

why the deserts and tropics are noted for their twilight hues: air pollution in

these regions is, by comparison, minimal.

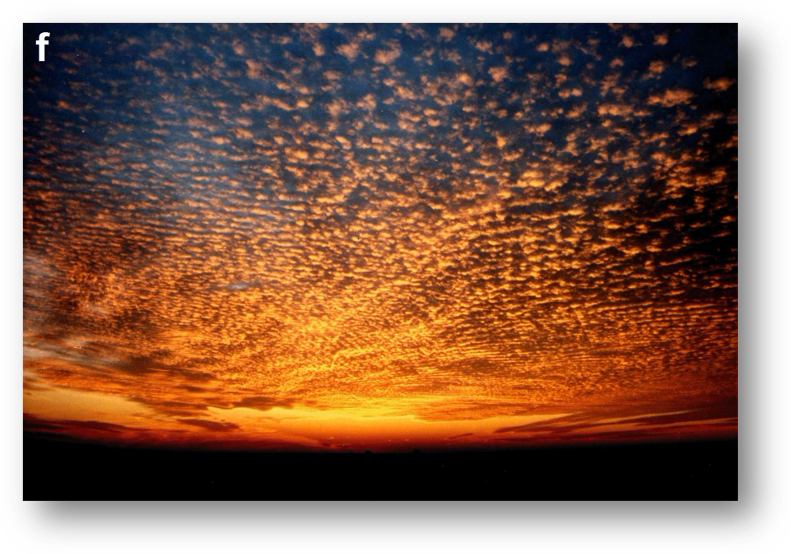

The role of clouds

The twilight sky can

inspire awe even when devoid of clouds --- as shown, for example, in Figure 4

--- with the crescent moon and crepuscular rays (produced by clouds below the

horizon) on a crisp, fall evening in central Pennsylvania. But the most memorable sunsets tend to be

those graced by at least a few clouds. Clouds

can catch the last red-orange glow of the setting sun and the first rays of

dawn, reflecting that light to the ground. But certain types of clouds are more closely

associated with eye-catching sunsets than others. Why?

Figure 4

To produce vivid sunset

colors, a cloud must be high enough to intercept "unadulterated"

sunlight...i.e., light that has not suffered attenuation and/or color loss by

passing through the comparatively dirty boundary layer. This largely explains why spectacular shades

of scarlet, orange, and red most often grace cirrus and altocumulus layers, but

only rarely low clouds such as stratus or stratocumulus. When low clouds do take on vivid hues, as

they most often do over tropical oceans and sometimes in fresh, polar air

streams (a polar-air example, with orange-tinged stratocumulus near Tulsa, Oklahoma,

is shown in Figure 5), it is a clue that the lower atmosphere is very clean and,

therefore, more transparent than usual.

q99O9vPr8x5kGRk7gfXPv6jofXrnPenOcpO/s3O2rk5JNNrV6u7e6e19VswjTajJJWt5rT0vq30e

9+4i3UQDF5ArdcOSvXnpzxn+nfNYwuufnlae/vyTT5k3Kybi9U7tenWwSoVJNcsOZd4u+vk9H5v/

AIIv2qPPt+vqf8f85rf2kGmnr15bO99U+m+r131ehP1aVr83vf1/W/8AkBuYWH+tAxyce3POR6jo

Dn361nUnGScYzTUbvVxeu90m0nZ3fW71vqgVCqndwu3fdrd3211ev/AH/aEOfvgden19+3qe/f1v

mbu43t8UtWk78291d3fP0avJ95B7CotW4ye7vd/nu3r09XqQG6jVyufl7g474HfIIJ69eM89qz5q

UFy3StHft6u+ut9fevfmb3S19g3DvLur28/6+Y/7TH0HzdTwOvXtn/Hjk810KDk9Je92TUn2vfmu

7+i3sH1Wto5e7bW9+ut+/S/2ttivJdrCdx3FRk4yT6gZ+mOnUisJ1lhIPmnJtq3NebvFyekrO+t1

q0+vfS1h3UTjaPM1vZaedl528vyHLfQy/MpIKrluPmx3H5En2457VpQpvEJ1b25I7c0krNy1s5K/

2t7rl5bzvung6kLqWvNNpdbvu10eiuvP7n/aEXDbWJxyEPU+pH68dcknPGXKnXk/fptxWr5XNdL7

csXJWe6b6uW2q9hObcVKCu73l/w2vrrrbYPtcTgfKcdvM4P8yfxJ55zzV8nNd35eXVpyd21ZJbvW

XZ/FqtU9Z+rVYauW8n8NrXv31j6rvdeZILlc425Tb16gY5HuM9uvuR3uSrTx6nh6ahhYUmqtNTc3

UbTlLn9onyt7tXktG4yl1mWHnvKXv892+r5nZu+l9dei1djgPEvxH0zR7r7BDDJeXkfltJsdBGjS

Hj5sHsc8ZznHQ187n/HWV5FjalPL8FLH4yNpVqcq6p4aDnacoTrxVaUZ8k1OHsqNSWjjOUFUU39j

kPA+YZpQeLrVYYbDTU4w5+dzny7tRuvP4rWummzDuvi7pcUTO+nyyXCJ8oi2GLeTjkvIDgn0HB6c

15NPxOy3E01Kpw5Ww+JafuU8VCrQlOV3JylLkny/3nSle7fImry9bD+GuY1KqjDG06dGcm58/Nz8

nl7OLj877Wu2ytpfxesbqXbeWEtkoQ88SlicFdgDJjnjPJzg4APHLDxIpSr2xmR0aOHnGd62FxlX

ETjNXcVOnKhh9G7804tu7SlFq8o7Zh4bYqhTvhcZTxc+eN03Kny6NvnbUr77NWau/Xb/AOFs6Fbw

SSXdvNBIv3Vl2KZOCfMyJe5HRmGffFezlvibkM8LWdbLMXHFpS9nTpKVSeIl70lJVKclTjJe7F+0

qRTk+aUranly8OM1rVIxw9WlXg7c0480vZJ7R96nqnfS1tPiWtl4F8RPikb1S1tPFKpf9xbRTfKZ

ZOon2DPPbDAhj8v3ia4cqwVfxCzBxzCpicvy+lONSGH5nZVeaU+Ss1DmnGT5WpxlyxktHGpKMn+h

ZPkGF4ewrnWSji+Xl/eJyk+W2sd+VKz3/upp3bPNPCfxC1nRNX/tP7TO+2VZljR3kVYmJ3xtG0hM

qYfiAEZ6fKRgfrmX8IV8nxSx+Ar1JYiLXtYyqTlSlCKsk6dSq48jUkkrpRXLpzLmIxGJwmc4bEYH

G4eE6FWDV1RjCUJRtaVKSi+SUXbWOq6tnq3i39o7z4LYad4dgka1WN5jekSQzTMQmI9spmRgRnJx

/wBfINernmCzvPfq1DKsLg6OHp1acsZ7eEJqSSk5KDhUpzjLmbkm3KLenNdtnyuXcK5fgPrUquYY

6dSq5Kj7K2G9nGUn7spL2iqb+8uWK/uvQ8P8U/GTxR4ju0lkt9OtbWPhbGCyYJKcZ/ezed5soJ6/

vRkdV7n9IyzK6jhTdeVOPs4RUlGKUVyxfM+ZpylaW0pSdmrxbWh6+AtlEeXDKq1K7lUrVJVZzV3p

eUuVLdNQhBWV2rrTif8AhKrp5I3urWCVcjzt8MRlkEeeeIe/XqcEYzzmuqvTpRaell3s/eu7aq+q

aTvfbds9+nm2Kqx1b1vfm62bbu+bX3bPTu3rdGmniCxl3pJp8IjcFXfZEgjPoRxgkjue5rOrCclZ

Xu72dls+a+t9kr826k3tvbfDZxOm/eb5m7O/q3fW+99NUl56tuFx4ckZxI55THyfOhzx+8Od3cjI

9OeKyjh6qetnfWLXM11tz6WktHvpo30R6q4kjHS70dvzbSs27b3tfqnre9eW90WRNkZJeNdnz+X5

ZT8Tk5J9T94gitoZdj3JP2qUVeyfI90+slq0299X5mr4qwkotcqXdvmberdnZaJNXvq7N7tXOZud

T05VKlbXy2Ekb5hTPPcjnGR1xnOCfXPuYXD4+nFfvE+V+9dLa8r62Wq0V27rfseXic8wlV3UG77P

RXvouazfz10+bOeuLvTYmQbUZSPk2xR+XJjnI5568dB15559CEFPRfEtm0rO97977aXvttueesdz

6JppX6+q6779tlZa6GTPqVkrMZxDsXKQ/wCj8p1yDHnnnn69evKrR5J30vK7s+n4tXe/z22FKp7W

9lv/AJ9fx12+8oi5R02M0ALY2DZy/XP0/HqRz0q6E1Fu7b6636p+tn379wnS5k2lqtGlF3+emz23

67nMXUJR5V83e8jjZz2PJ57f/q5NezSlzX87Pzbu23dWve2u6PIxFNx76311VmmvuT8u/UqPfahA

ipF+/X7mJOeuenA6ZP5+nXSXM9U277u+vX0ve7bv1emjd+WUW3da38/63IUl1l2V1WeNXA8znzEH

Hp0HTOeaqNSd7vvdttO76bLrt0/UcYPezb/Lz6/c133Loa5nw06sGRx1BzubHUDPTI69zke/HUrO

aa5nzJpK17pcy2lZdF1fpuz0cJr7s1a93J3+e+9t3qr6u502hC2t5ZF1D9xjY8O/+KQ9CCeD3yME

kj1xnxKsbuSldOz30d3Hrdq+709W11X2eRUqampTaWqbvZrVuW0vVb/i2e5aPr3h+yszbrqFrHvM

crrcOmcy/wCtQ+YRk8ZPPHIJz1+DzClUjCqmpJNpSvHmTT5nJJtSlHV3bdtUrq2/6Io066o+yqWc

VJNRqOk1K3Mpv3opq++r7dDej8Q+GntHWwvrRmdWiwg8zlOenXzOMgZBmB4Jzx8v7Gm1ONBO791v

2bdrc/Mk5J3lK7eq95JvVWSz+r46eIpzxFSMlGTmn7enrKV3/NflbtbrTei035XWdVFzGdPtLiBY

THukuHJxJ1AERAHBwRx3Y5wa6KGExWFi4Q5pQWsqk03OctL2teKbdlyrf7XVnrKjTgnUnOKnO/uq

UZct+aylaTTk3dt3b6td7GgaxZaLeWsWofvbVC4iuZGZgl0ykmSWMAgRxxberL6HsT2wnWVen7ZT

cFdRkm24z253Fte60m9tpaL4jHG4Z4nB1qeGxEIVm4cyc4xdSmm5Sgpt2jOTatstVdq4niDUdI1B

PPs79pLgvIklusj5MfRQkRwCM8gjGcA5rswbpzrxlGVSU+b96qnN0s4uF9dLPW+vxe9pI4qlKrSw

s8PWjSUbJ05Q5XKU5Je15pRdnLm3bTWujeqXgGvabfT3Ilht5jGItuUk8scSD3BU8nnrgEjJr9Ew

NSl7OLkm2oP7dtUtb62d5LS+7avqfnOY5fVnUb5bpyUmu7b5r2d7dL366Xeh3OieIFsZltpdEuZN

tlH5lynleVLJsBzmTysSmdcZHI6Hpk+VjKslUs4ys4Xv3d2rb3u3r5735t/oMrw0acPetd3spe83

3bfvX1e99b7GrDqXh19VS8uvDl0pE/nyyRSR/OUIz5sWRFNngTDP785DEHk+PWrQhJTnCdnJubi9

7Jt3V5Xi1e/Km3d23cj6DC0m+dQcYzcX78o8y5m73dtm9XF3+LVp7PtE8SeDbOf7VDpcMMg55jt4

9/OTiPy5Y+voeQMnGTXlV6mDhOVb6s3JJu7cOWV+b3p8yab1Uvdvd25Xo2bp4ipT9lLMVBN2k4U6

qkrNpR9pCVOct+23cztX+IOkTm3i0/QEl8lw7zSrZJG7yfuy0Zt0JPlHnpwRgYzXNVxdOpJeywfM

qbk5TkoK8m3B8s4/bTaunGTvffQvDU3QlVdbMq1Xn5YwUZV0qXK9feqTm5SbVpaOzk7Stvdmukkk

SabT1dZIkRViSONY8E/vATngHJH4jisPayl7V1ad1OMVHootO0pXSvaTT3T+J7t3frQfJTtCtLmU

nUc6knOc07vlVkr76N63b8xNLv8Aw5dag8F1BKfKj8yIxE7FZJACBjPPT0OR0648GrhsFWxb+s0a

ukeak1JyhGSfeekHeMW7K0rXu9SsRPMfqy+pYimpuVqiqL3pRlHX3tt/PW/Xc7S88RaJDACbmG3O

9It9w2EJTI2YTjrnGfmIyee22IkqMLQlyttQXPH/ABWhyvrFO0W9W+b3nZX8CjlWY+0cpxlOCjKa

5JRjJupqpc9S2r1W+rXlcl0rXNCvpHVL60dl52rIDjHHmHGRg9jnHJ49csPD65OVRVYcybetnHWU

uaeqt70rO97X1erijPF5fmNGMZRpVKkOsouMt2/ddpNvV7d+7Ru6rqdjp2mQ3Vu0U26QgWvmxyST

8ZkCRn+eQenB6CsV7ShhoVISjOTbSorkcqji5OShFtO+klZta27vm83L8Bisbja2HrRqU+VNvEOE

lClf4faT2Teqa03Klt4y0CyVHvb21gNyqF43KtsbORG+z/V+X0Jx/rueuMlKcIKNStVinWgpTjrK

Sla3vNJtKCbla6aqXb5rDxeQ5jUlONKnKToTly1ZTjSc0rpuHPKPO5b8vNfkv2NGz8VaDqjTLY6p

YsigrxLE23H3clSc4Jzz97gg9a0pwwuJ9p9Xr0kkrN87benPaS95X1jJSvstJa8xx1MmzDDKEq2E

q1J8ylL2bctf+3Xv1tKy1d9bMfq/iPT9G0pbpJbe83TPFHvRJYTImZAJG4yzF2985zxkkjGphKLl

RUcQ5VpqmrKai6fNPmm1f3ZSbi3fnbjBaXbWeHy6ticXP6zGthKdOlGdT3pU6lprktTVnpJQtpa9

230Myz8caEkC+dp+kz3E+Hk228BkT5e8bxynPfrnJz0OW6k8wcLzwGHq873dOm+R63bT5rr3o766

SbejTMTl9SdV+yzjF0adK/JF4it71/eld05wd91qlr1aNUfEPw5Em5LLRHfosBt4HuEyfL54OQSe

wBOOozz3xhjlGS+o0HG+kHRp88fiWrb95y3ajbVvR3uebPKqkpWnnON97WUo4mqozdnJxUdGnp9r

Z99CtdePtJkVXFhpkAAHmGK3ty0m/HBwR37kc5HJ5qJZPj5q8qGFpu7UlTpQ95N3fvNfPVOTb6q5

NPDUqTl7TM8wq62ipV5+6o325Zttv5apK73MqT4hKUY2jaXCnllzDMA0m8/8tPMEuMnaegB69R15

avD2eTd4fVoQu7wlTnUm5yT/AHjmqqTd7PVN6O8uW6N7ZNH+PiMbWqJpJqtGjHk/k5VGbWqd5Xb3

0Vjmbn4r6wI3WB7KBVO2TZESBnnEckc3J6nkY/THTh+Gsc3aU4U2376hSe8m+a01KzlpfWz6cuqT

UlkNNqapVKklrFVa3tOZvurR6uzd7W1u9UcxceOpXim84288kuDHud5MPIfvyhwPbBz15JBNfQYP

g3DKKdRqrUV5vnblzdXObba2eul1vrY5MbxA4Plw8VSivdiqceXRSslpZ2Wu6f3719B8Y3lrPI9v

cBWjmDmF/wDVr5n/AC1t/NBMAPTrgsc9a9SXDeDhOLpxVNxvK8YrrZ3XMr3W6bfNrvZ3fnviGtVi

6dePtYSVpqa5rq7dnq7q/Rza72bV4tZ8XXt000kjMI2cuI43wceksh6Z65xkZAyTTpcO4KMm5QV5

e/tbWN5N3s30tfZ2t5nNiczqYiyp3hGN1ZaJdklF9rN921bz5+HxBq3knyLq4hs1b54VuJD5foeB

z68c4HXrXXLK8NbljCKintZW67XvpzO/mtlor5Rx+LS+KUuVu9nq9NndqXbRO731tr3Np4slij3x

3Ue2dIzc7AUfMY6iXnycyn3PVuMjD/svC6vlh7z15Yq6s+ultbK9rre+pths3xEJpVHzct/ivb7S

2utbtxu9VqrN7403i2/NyzrqTyQ+ZlAk0sbRkYyS/mcndyMk4/nw1chw0lo3Hp/Ed++rb3eku/Nr

rqn6P9vzgrezgk91KKSlre7Vved9W2tL6PUdp3xA1GGTYmp6qI/M2YNxP5eSGwT+9657noeT3FcM

uHHHmUMRXhe6Vq1SSu23fli7Lp2V/tbW1/tmhVXNVwuGqO13z4ejNrfS8otK6bu9b66Js72z+Kes

W4WOCcSCN8k3J+2x+v8AHiUA+5/A7q4KmTZ7ST9linKMZOUVW5a7d/ejdStL1XOr8ykleUk+Kpjc

nxk37bAQptp3lQlPDp230p2i5LW0Wm9XqrnU2vxVCQPPOtt9pIkU+asZLHID+XB5pQntksPvYOcV

5FTAZ7TUnKdKc5c8bySlZNN3jT5kld3lr5JPXXp+pZVX91SxNGipRk4wqJ31abdS3PKzWt5ap7t3

NOH4oCFpbuH7C0qIhVCkYbEhKeb5cmPNz83bOeck5J86tludU6kqlGFNzfvJNqUJSk0m5OT1fT3r

yd37srXCplWSVoKnLG1+RtuXLOaqNbqMZWjZN63XNs7Jq5Wl+KV1cv5n2l4gU2FoB5BQZ/gjScky

dSJeex6mtcPkvElS7lXhFzTTcF9n3lJRXNeM29edu9oczWvKs1gchw8VCGHniE5+0/epVOaaT0lK

SbdPvC1t/O9U/EbULl9puC8T7EaYy3Ek6eXj5/3j/vxF35U8Nzk1usoxdRSVerO7STm3J6xbd+ab

vK1/d919Xd306Y5dgYOM44OCgpSailSUeSVuZKMEormXRcuut+qsWnj24tHYyXks8LuzxxsXDb+f

NMhJ4jLYPcdf7xxlHIqVHmcsRUk+Zz5alZ2lLW6dru7bjzatv3np00r4LA4iMefCwp1bckZ04xvZ

bNb2kuknrra+99LSvH9/qWpLZiOKR7om2gbZt3NJgpgSjvjOA2WAyc448+tgsVzSpzhTqOtzQg4x

aknK7p6SkrtRtbfVSs+azVz4fy1YOpiY+1pRw1sRO8nLmhHWeq1um1fRrSSv0fqunW0xFyuoW2+W

C3SR8R7Osn5nchHJPXgHPB46OAlhqlaniaMbwjzScU1zJSe17/ZSTTWrtrpG3x2NxFFToSwddqnW

rzhG83K7jG17p21q3VtNXrqcDqfhmLXrlzoN3seWJ/MsJAd0XGHcdSI+5yfmzjk/MPKhg+eq55XW

5XOE3KjVTdSDvJ82ql7rfvNS0tbV3uvr8DntTJqMf7Yw7nGnOMqeKg7wqu65I22dRvrpbtKxo6H4

G0jQIGl8XahArTofs9usqIxkTIMj58ySOPBwOf8AXDqMmu6nCWApTrZzXgpTScYxlCmr0l78ptxl

OKfWUvd9pKTfxWfHmvFmZ5xWjDhrBVZKnK9WtOnKaSnf3I/BTnUb2d9KSWzvZl/4F8Nyy+c+rQWZ

bDxebIoLxP8AvVjycn5o+xHOBgg9eDMcXhJ0KDnmCwijJyU6lV0ozhKfMoKV0vei7NaNJqTSdxYX

irOIw5Vlc8VOMOWpyU+blqRfJKbbjdLnu+V3V21e9rvuPhnZSWTR3N/a/vNgil3yxxOR/wAe+zBi

PmSDofbrjivXjzTownLF0YtOKhU52oySTVNJrlk5z5dZWbutW9GZQ42rPEKNPA15Qi5OeH5ISqRd

17Vyac7Qg7PRX3s9dfPR8ONe3zyRabOqI7tEV/eQ7BnZjoYuec5OB1yTSwuZ8QVaOIccE6NKlKah

L2sarr09VGT92Eqbkm1Ja2ezkk3L61cV5BCVHmxVCVVxXNGTcZxqNvnUVZ89rStZKzb1ex3uhaBd

WlnHcQab5lyrFZ5XUvHHGmQIwqHgcBiBzkGvJr5niXZ0aUniYNOtOSlVhTXWCirc3MtrpN6ys22n

83m2cUMRiZ0auO5MO1elCMnCc5z+25y1Wnu30/K8mteEbfxDJFHd6OwjCfOxHlpHJsG5yvzDAO7u

cdckgEctXH+2rKDwOJpxleUpOpKEFNJ89VQTkmle/K+bmlJc7cdXjl3EU8qpz5MwpVHOStCaVaU4

87tC7ST5ldarRvaxFo3wl8O27yTmwube8DbZCs5RXRMDlSZM47jzWOB3PJeFnSqxnUTxFKvVl7Gb

lWdnyKajLllKqlKLk5c7nzyfJJy0RpmPiHm0uWlHEYaphnqkqEXJPp7y9nd6WUlT2doyujsp9a0r

w6U0+2iS+uE2R3YQxptihQxxeZJny5Dn93165Bycmvk+IcXjssrQoYOf17F88PrcYVadKVKh70Yy

nLm9lKekqa5nC99bO3N83SyrMM8UsbXqTwtKXNUoOUZ1HKrVfPU5Y6ygn/E2aSut9CG4+IFypxaQ

wWdqFaPN1EZgz+0hlA8vjJGPfc2CRvLi/PHhnDK/qtBckoz+twhUvUi5c6UlW1jCUJe7aXMrcs9J

OV0eDKTTdepUxVdyU2qMlScYaX5qbp359bp+bT3J7XxXYOZI9Vt/t80mwwtFtgRWOTJwXllOAMEk

np0yKzWPqYjBuGa+yzGvKzh7HlwyUleU0oqrUqRcOT3ptyc7r3EnyLLE8O4u0J4Ct9UpR5/bqp7S

tKSWkf8An3TV3d3/AJt78qusl9pNzulMNxZeXvBgV0dX3DcZIsMevI5x3yemd6Ga5ZHB1VLAfUpU

W1KLxdCrKSmnOU4OE5ci/iXvySlb3o7cyhhcxoJUvbUcU5uP72cJQlFxuvZzv7zabUrt3+8y4Tp0

M0k26XzB9ybeTs3cA4yOMn1weMj14MBn3DuOqVa9KSlUpXcpvEOMop2XNySmmoqV4qW118Wqv6NX

67WhGmowUWryp8vxNbLTR2trreKb1fRfO06ATXEpaQNl2jTLzNznBHsBk85H1wK9F5nl9ONec5Tq

05XqOlTTqVLpXaUYvmk25fCrt1PhTkyeTGVXTpQjGDj7qlNuFNdd/Pvd6922amiWngPXpZRq+o3+

j3UGTEPkVZyW/gCJId5jjyRznp16+fOXBeb4Srhcz4kxXDWIoTvKrKL5pK/PFumoSlV5qTUbavma

s7pt+fm+J4vyenB5dgcJmeHq6VW+eUqa5G25ydSFoKpUcVu731W53dl8HfDusAXlhrzT22cFpVQE

8ng5wTjP9QDkE+DDwzpZ/TliuFuPMDmuBpNUp1cVgq0a2Hm2+eM+bHUre801D2cG+ZO9ppHyGL8T

c7yxzwuMyhUMRa7jCUpK7dlrrrtbzfR3Ou074JeHIGUC9S8/vFgxL9j8gcd8cnJz64yeKr4MZvPF

RpvjHA1qCac44PLnSqyTu3GnVq4uvGEr2SbjNXbXLZpv5rHeKmeV4yaw0sM3tZx0e+tSUZt6a2bW

vqjqY/hX4VhKsYwpHDbCck7f9ktnncccfhg591+FnDOGUKeNrYzEtRXPbGYlOU7JPWnWUdHq+VJ6

/BBbeBU8QeIqkWnUk7t6SSd99rvm7PV33bNSHwHoEKbVI7gl1frnjgk8Adcg7iScg5ztR8OuBKKk

o4GcpSv79fEYirKL1TUZVqkmlorJPl07uTfm1eMM2qy5m3fS3LKC++3L1b2ei6u7GD4aaFKxdvmU

/PhkIGD2zuz36dc8cdK8p+FHDVWrUqU6eJpQlJyjCOLxUYRvzSfLasuS/wAKp6uCUUo3ujX/AF6z

anFJaNaXTWr9ErrTTd323+FE+G/haKXD25ZfaSQE4GR/FnHOQOTnv2rvp+F3BCpXxccappzTjDHY

uKVpNXT9rK9lZN8q89RVON8+q00417S+ynGLWnnvov8ANq7d9eHwb4dsJP8ARbIjAGW8yTPPcZPP

TGR078kiujL+AeDcFWhicuy3FVsTG8o4itjsbKVPSSvFVqrp3eqfLCHuq8pP3Tgq8TZ1jIv6xi02

76ckXura6NtdbNro0lub1tbW0EYW3j8o88sw5ye5J5yM44zwO3J+nw9CnQilgeek7u6lUlJp6WbU

m0vidk9Hfazu/Gq4jEVpOVafPftGz8tFp539b6snywYF1ITk8EZ6E++euBwMnPWvVp1san++pRe1

3orN3956p67L56szaUtknLZ3XX1/q3mROqyZWSQES7uGU55Dc+xBP65Oegj21ShUcquJaUujUm4q

93Z7Ra095u8k/eLTlT5ZRjaUHo7p3s7tatfffW2rPOtR8C6dcTMz3zxGRi+Bu43E+hxkE8ttyc88

9Pk8dwbk+Pzv+18XjK1WVm1TdWt7KKcZRm/ZKr7NzUZaycE01dxbjeP2uC4rxtCkoRwsaih7v2Vd

2Tvd3dtOj726N4OofCbSb/dGLheQSQQR5g6tllLA+2cH5cg152N8KeHauGoQyzN6uCxUJT5FG1dO

U3KTjOdVzjOPNKLvpOMYqCmopRPYwniLmWEcansXo0l77fLq7aSSb6X5uaOrfVs8ivvg94Mt11O4

v52/0AGSfyy6sysflaMSCXOeOAD2yCRivmKXBzy/F46jm3GuGo4XLaHtZunl0qNaqnDnXK6uIqKT

vzQUIwqSlJpRkpaP9JwnibxTXlgKOEowaxjVOjzpSs1dy5uR09Vrvp1V2cXJ8CdA1iV7y0aUaddW

gNtdTTEzlwSBGyg5ii8sA+aYwp5+6DmssqwuJzSeCr5TmFR5LVjjvb4jEQoSxWFxuFdVeyxOHpRh

KMatT2bjUs4qPM3NXhf6T/iLOa5fGNDFUqVTH0cRKnXpU6KdP2avzThNv3588m3H2t9fVR8uuPgj

qlv9quodQaSxgDSKoJmWZlk8tNkKnDeW2T+8hJAzyCAD5VHivHrKqmJdF08DGvThWqRxUYUalWOI

jQi/YuftJt1FzRqThCCjDWak6cZfoVDxVy6r7ChUwkaeKqtU22nSVFSi5T56sly+8rNqnUbTe1lK

1jS/gz4hTSb2ztZzHd6mubu88pWuvs658mBCvzIIt5JYSg8nJhwanD+J1VOrluX0K1aONlThUw+H

jOtWxMMNTclSilCdRUoRVWdTkjrT92/s1UU8cw8TsjlmGHxGIpc2Hwb5aGH9rKNJ1m5e0rSlo5tu

HutxvF6p1XqZenfDXxN4FhnTSLOW7eWNXkme2DXWyyk8xo2nZVmCRyb85mEQBIxivSyzxNrUMRiI

RqUcJKrOEcVhq1J35qT9rHmUXTr0klDnrU4uLaTc1o2uutxnw3xLKisZWpYOnRfs401Wfsn9Yi40

5cknKE5uDfLeM6nM2lbr8h/tY6Jf67Zway2iapY6rZWkK6ylvv8AKmslkK2rSMeUjkupyxG5iVY/

Wv2/gzjOOc50qmKeDoSq0IYenzVHNTxNKDnKvTpVIRqUpyoXvFzqRsqbUrtuX3PC2WZVVwEsNLG0

cfg1iKjwtSNlOMX79SlNRbUnTajJcsb3c21a1tr4dfDn4fXPw30eHVLePXNLvYL68bT7tkMcOtXV

tFbX0EyD/SxLbTcAwn9xcg3RAPT1cTxrUyvG4hYzFTlyTrzhSUaahTqqMadB8ic8RKEqUoVKNWlF

xcJqrJwX7oxzTA04Y+pg8Hl9KmoSoSliKkZVHUw05c8q0JrloxvyTjyzkmv4Uf3sYzPNLf8AZ0m1

2y12/s7a60yfw7FNd6TaQP5I1xLa4kjAaR2zFg+RMZZix6Ehuc8uXeIVSjUnKGY0PaLC08VieZTc

6EefDqsqThJJujSqVZuKU/acqp/FJyXDm2Q8NUa2X0a9Xm+uV5UG6ag4Yec4SlRddRevtZPkTjJy

TUpOCcVzeAeNv2ebzR9dtbe2MN1d6roEOv8Aypc5t5pjL9otrd5fO+1TRGMedPDzkgEdTX2+WeIl

GrgPa166lShiIYdyi01KNSMakHiHKFFQknJxlGMqlONRTpuq6kKkI+QvDWhmWNqYvAV37KnWq0Kv

OoRXtKbUJXjzztztxdPm5Zy5oXhG6R2mq/sxeIY/gpqC311Hcy6zpWj3Xhm0sDJ9ok1O8ktJFgBu

pFgV4rUGWbM6288RPzEjn0KHiPRwWYQrV50qWBli1P8AfOpNcqqyeIcvZ0L05RoQc0vZ6c0ZRnKb

jE5MN4f5LjMdUyehjVOvQdX63eKjTw8KMbTq1ak6lvZud4KXvvnUrqMVeTIP2XfFlh4e8N6vrN1a

XFnoSWlmbeGXyJobe32RpahiMHypTmWdYBnHS5yK8XE+J8MwWMxeHpV3hKtSeHpV5VKUvZylUqTc

vYp+1gp3Sg5KT5pRu4Je76+B4C4dWNWV0MxjLFyjzq9Go4VItc3u1HBwu6d3FXjKSve/X0v4rfs0

y3XgzRdV0G+t7Lw1o+u6dc6nbyI919otdQktbed9MuJLqMpF5khKg7uhznknow3GU6EK2N5PrVGe

Fr4fDxhWnTp0cXVh7SnVjCpTq/WKMqkfYyUfZzpu00pQm3T7skyHhrF55DIVLEUMbUhXnCEqfM70

I1XVhWtP9zU5Ye0SfOn7yUoz92fAfGbQNKk0z4eXOkWUKanrGpL4T0+CwHkWcckEf7ma9xBNGZTK

D55mntxb24uDgrlq5+H86r42OOrYyVGjSwOXVcTjIRilJU8LOlfkTnGXtK8cS6sOTnlKXseZPnjK

Xr5lwE6mNrYPCc/Nh1Go5ShyxcKkKk003J3Vqdk7NS1ilJ3RX8CfBJ9SvPFkWovFfvpVnpa6Vi4a

0t7zUbqWRrqBBEIzM8Ij8nj7OcnpnmuPMuNKEMLg6tHkoTrrESlh6s17dqNfC0qLgpNud6VSrWdJ

TlN2XK3scuJ4IpYGNBY9yXt3Pkqwi504xp0+eVWq4u6gm4RcuV2cle6u34t8V/hPrHgDxHFDFafI

+nLqktjJi4aV4sSy+WRnyrSGIYnGCRjOT1r7jhziSnj8M6eOi6WJo16VFSqOKio1oRdPncWlUnVl

LlilJ21g5XUrfDZxwtj1R+tZZUeKwk+dQrUql4uUJSUlZ25eWV272ktJxumeefDS21fXYfEcdzZ3

FlM+l6he6e9tGBZ3EenedcmK4/10PSL7RDNMePs+SDivtcf/AGRQk4SrqrKGHcnGcuaUakaaqVIe

9TcoqVo62ajOMVzc0op/J0cDxPNuLlV63Sba1lK1/wApK2t9LkLeHJYfhtp2uzXTSaPJ4vt7+8m+

zyO9vHLHNbRW/wBpGYCZzDkGA9SCexreOMoOtLDRjF4p8+FdKDcZwcaEqkpWk0m/ZxnVUJN3vFyf

u2M62TZ7zOVT2tlHmTbk2vtXenMrbPXVdXrfzbxlNe/E/XNF8G+Cra51DVrCXUJLtvtEVol8kUXm

+XBHLiKGO0ghI9gSOtfTZNgsHlVOpjJU+WGLpxp0pSiuaU7yqKTi3TjTioRk0pSi5JWfvJOXzWOx

3EFKEo0a1dqnL3ox5nezV1Ja3Tlq29rXslo+I8GxarrHjSYXOqXif2TB5lxFJdzxX86WY+yGy094

gWhkt+kIyBBbr14wejNvqGFyWL9lhoQxOsJ+yjOk/aONRSmpRnGcq6e80oSndt2spdnD+f8AE8a0

pSniE0lFx5Z8smr2co3UHyy1jdXXNo78p9N+G/if41+EvinTPGWka1favqXiWObw0vhvU57nV7y8

hiEc0U00ckwzFBc+TFGDm5Fy023i6JHwcMiweZZd7KjSy/CfVKs8WsThKcaMYxqSjGdKpSp03pXf

7yMfaxvKjRai/q9z9Tw3GeJr4SOFzfD1KseaMbz53FVIyqNVI2XPCfJJpyi4XuoSk07P1PwP8Y/i

58QtCu9efxjrMlzpOsXl1c6No8t7YfYreILJAzw2rxwvZReb5IMxzN926+0sjE/IZ7keX5Bi1hqM

66hXw9Nxq4jGV6spSqXjWxUNXCjOUn78qXK6Tf7qNGE0fY/2hi8TQU8Dw/hakZqdKWI+r4dzbptp

xmp0ue6aSano+VVF8S5MHxdq1/Yy3niHVdQuLfUIJrbUY77U7i5vOPN/egyyyieaGfzh/o8B5GT1

Jrfh10cXOMYTliMRzwjSSu51JQbclVlG8ubRuUp62Ws+W9/gMywWOqRnUx1KopzlN8nJJfE21qlZ

K9723emrtbz74T3+qeIfEetXUUV1caOt2LfTsQXJsJru5yL2RA/7oEQf6QLfm5FuVyQenv5+8Bk1

HL44iVGGKnTqTxEOenKpTpylGnSU4pubj70qcql+R1Eo8z0vrlmRZniKbqU6c5U+Z8sJR1dkm2ua

N3Zvlvqt7OykbPxp17WI/B1x4Sllj00+G9QbVYdqPHcXkjkxeVH5TLF+5Mwx6nt/ez4RqxrYnC0p

QhicNUqYim38XJNtpym3zJpKNS2ibT0lprz8Q5PnVHCSnDC1aKcVfR2cUkm+aV3quu7al6nnwtta

s9R8H+IZ1utZttGt7TVtZhs8iOy0K4SKMGaOQ+TPN2nyQRnPavs6WOh78PbR5oxp+ytFTcXCtTi6

fMrOMqkOaLctOdrmaXvP4inlWYewk50nFzb953bbu7yatzXWr33969zc8dTzW1x4XlkvTNaT6lZ+

JNNuA8kctpb/AL2X7NKf9SJbQRZGSfz6n1p1MRKampxdNTTSvJRqTpxjeLlpJPdxV1onZX5uXF4O

eHioQhUlJtQa5Ztt311atZy1V9Fq9m7RfB3WvD2ia5P8Q/E63t9qfjDWtb03T3t180Wun26t5hki

lHnytdzXCJwTlhbZ4Nzjlz/GV3TnhMPBTqYDDxxGKg6tNP2+KpxlKbcqjUk1Umo83IlGlXtKp7tN

/oHBHCTzKcZVqcqd5JXlSlrKDnLlTasrcs5czsraH25+z8nhHR/Ck+o+JbGfxDrs3iTVhYWvm+Zb

2VjLgWv2xZCiy3OwloTm4eBDtwpBWvw/iLNcqw+Ir+0wVStifqeGhSg4WwlqeGiqteUZP2c/aV6t

WK0lyypObpe/Gcv6JrcP5tRo4fCZJisPluCWFVfGYyVKaxVWssRK1KjJxfIqdGNB1pWhzOpKMas0

2fTnhn4a+JfFcGs69aafDokukeVJarLEIYVZpCYPLcjypZPLJzDN2J5Oa/HP7XxEq8sbgJ0JUcu5

K9erRlTw1OlLmbhQpXg6cqnPGUr1al3TTU5Si4wfz+ecb5Fw/Wy3KsTi6mawzHnhiJU5upWmlF+0

c4L34U+farT63Vrtt+D+LbH4kaN4z1Lw/pms3k6Xvhe3sLg6SZ47rV7y8uo/smmaf5brLFeKZMxX

1p++ngiuLdyPPRx9plea5dLL5YhVvb4jE42jRqVlN16UsLDDUKtSVWcoOdej7SnGhOnNL2kpXTnS

qV6dX9U4fxPBmZcOYTOcflmGpPDZ1VxVJ5g4ToZdQw1Gp9YxmKhOEqEsNKKarUa7UYTqUKlpKhp9

O/AzwLc/A7Gr+PprSaCxsjcanLsS8udKuLxZWjjZXPmrf21zKfOmQLOf38UKqMLP8njs/oYvjLCV

KmVzngsurJYzDclGtZ1sNOGDcqcXJ4atHExoP2LUa1D2TqSbumfh3irxXR8VVLLOEaWIp1MVivY4

KHNPC08wp4aVONSqnFKnLB4jD0rU4ScqX8KdWUm37K3d/ta2evanJaW+maZf+H9KuTdgTCaK5uLS

3EhljN59okhQvEY5TMtsPKLDLXEQnirq4vwOP4jp4SnjsrwuX5csZTqUMtw3N9ZUXan7Otj4xjVj

UqOVZe0w8Kcot+zs4OX1jgwf0fKmWYL28szx2FznF0fqtT2ThOhhsRW5XCosMqUK0lzOUVT+syjU

/wCnNX2VU9Cu/wBov4dHTE/svR7i7neNJJ7eO8jMMAJSUiK6ZGNwo94oMNEMZ587ycLgMiyyhSpY

LgiWGxFV1IYyrjs1xE9Y1E6KpV/Z18RWUprml7WlQ9muSEYzjzs+Uw/gvxp9fm8fmVGhRjUlClXn

hpqpVa56ceahGoo0ZSvZvnrJ87u3p7PW8K/HDwf4xvPsunaBftJbWyzXKGYM8bt8rqVjiHmkYJMh

m/e4yWz08rilYTGQwn9t8IUaknWlChVwOb4n6zKMY88pxUMHRrVOaMVKcKlbZOcneKlHzs/8KuJe

HMN9YxucYWMcTXnToP2U1eDlzRcpurJQ1aXIqT9nzS6avz34l/Hbx/Ok3ww8MeGILW416S8tLO4j

SRbtraSMPFBNulgVfMQTTT3Bighnhlht4cHzzcfTZHWhmmQUsgwuBw+V5VDE4WU8twsK9bMaznWp

140JYqqlzuriXOVecaEHVpznKtGlT9vOv9fwT4S8I0nHjvOs9q14ZVTo4irRqSjPCRxcW4zrwtGr

VnyVPZwp0lUnVpzhVq1NVT9l+fUvhW88A/Etr743aLqI8P63p7aZ597PFfaX9vkE032iWGDzTIGh

HENuvnk/v+uVr9awyw8sHhsrw1GrhcRgMW6+Iw9GlWwmMjhZUqVOFSjWi4/WKNCdanVm6GJirNU4

zm17Kr+0vMZcQ4WriuF8fhsXDC017L2EEnGnFqCg6U4wnR543pxnOmoXaeqjdefeC5tG0Hxb45vY

P9H0m0stQsdFkWEO9wZb8Sx+VvizlrSLM5uMZOM46178qlKthcHRxmIbnXw9SU51Iub5owpxpRnD

SKnUvLk5YwWsoXi5KJ8fnVDMcPiKdRzrVKicnUcXUkk3or9Htpa7s+974Nz4mutTvn12eE3upztG

FtoT+7S2h/dxmXpkHsASDjJyTisHg6NOmqXtYQjzOU1OilTc+VXWlk7pJJRSejcpXba+dxGOxiUL

/WVC8lGrGNS/NfVcuqTb+01HXXSx3OjxzW+qzSsyXUtxp8d1O8sp8uygQ+ZCJ5ZAG/15Nvyc5JYE

c446ODwdWEI43Dv6rGDqwlSreyhH2yUXOSg+d62hZTupO7U7Hof21neAVGpOtL2WqtO8pJLmdrye

zXvPm0vZK7dir4W8bjRtUcS3015cyXFxclrPMkioknmnPnt+7ByQO/fnkDzM04ew2Nw9pwlToQp0

6UJKCUZNrlu+bkc3JK66xum7/C/awHElXFP2WIjFwmnGUZRjL3ZXvzSta71lZt76Ozu/snQ/Fcya

baXMd5cJcTQx3DwxzlpIo32yL5nlyAmWHzB9oIyAeepFflOb8GYCMIVFiqM3UcnKlKjCbhTf91NS

9yGtRu93JKNtTrxWT4fHVG/q2HdFpKPNTjbnlFc8VeLioysuTVa31tq/UNIj8d6tpba1pS6ld6b8

5M8c+53aCRvMULFOZC8Z+X73PJOTy3m4vw2xEMJDH4fA0sfhZQb9pQp05NWvGcFTUqnPyJc0+X3l

J8sU2tPjcxlwnl+OjleYSwNHG3j+7qUUoqNWPNB3lSUOWd09vO9tSzpniLxvYsXtNT1iJ7jhoo7y

7EayfMMiMSCIyeoPJbIOSa+YlKtlaWEoYrG5ZGD540sNiK+DcpTtuqM6cryvaWnMn7krSTRhjsl4

WxceXE4HLasKN+WdTDYdzcXv7/J7Tkbb1vba/S30B4a+MPxItbpV1ayh1K2MUatbXGmGKVl2/wCs

zBCHySM5MU3mnqM9Paw/iLxZkuKp08XipZpSqXUsqzTB4OmsRG8uX2dSlhKOJ5+ZN88pVI6T5oSf

vL8cz3wz4Hr0XLLsVPAV1OUo16OP56UZXa5EqtRx6P3faUuTe9rX9BX4peIJLmFIfABhurhGaGcr

jauceZsaGMkknJ/5anOdyivXxvi17SaS4EyqjmCjeilCtPEVJN6unRjlcZVE5WvKD1m/ju7Hxr8P

smhRq1KvGKrUaLUalKMo+87X9nzxrTStv/JZbX1N6zvfineoTcWlskUzbY4/s0IYxngjazBxkEEE

nJPt1w/1i8acZQWIw/Cqq4LEU03RrZThqVFr7KlTxeMjiopv3v3jXfa542Jwvh7hZL2VevOrSinK

axFdpya3vG8ZK9721d7anRWeneKrRWuzpFnFfYICGODzJGI+9lQ2OobAPB9O3v5JlPFOLpV8zz/h

LK8tr0G1Rpwo4CVSq5RtFtUVPkXMmlH2s33aXNE8XFY7h/FSWHWYYieET5nL2lfkgm03zdU7Xu2l

5ttXIJP+FtRsZAbKAFsbG+wxAAHIOGeNj3z0wSxwxzXlY3HeNeHxWKqYHh3D0stUksPGMMiVHlfw

yjUr4nDYqc5c655SglzK8YxXNOW6/wCIcTSptYmvKMF70Xi6jf8AM20pLs+/V2ehe/tX4ktB5V1Z

adMoxlnlsVJByTwJgvPQcAdC244rijjfHD6nWwUuFsDW+tzjatVjk90lJ80ZR/teNKTnzRSlaLSU

rqV7rjWA4GjW9rQxWOpSd/dUcVK7vdP+G27dnfVrazb5+T4hT6fqbaRP4e0ltZMalYQ0QklZUyoV

QrKCSD/EzYGAWrL/AFwzPKMXLJ8/8MsoqcRVqMZ4ipRxWETqzp051acnCjTxVKneNKc+X67Vraqy

nKaU/ajwXRxuBWZUs4zL+zFOV6rhUtTjKfvOUua/VN6NczTe9zHTx98SNY1KGLTo4bCKRzaiO3to

GZDGZVZzJJEyxxsqfeJXGPmJPI8GXiRxzxTbAcKYN4f2MKSnh8owFDERSrqXso4rE42jUo0IytNU

5P6sm4SfPL3j0nwfwNluAqVcdOrjKtOn7eU6uIrKM3JRlGMYRqJzmpT030vbW9/cNM1LwpYWtt4e

8R65HdeJboCSXlvllY/MN8fyDy+VBJUMR8qjOD9DSyrBcNwpYHjrO6eI4kzhwq+xi4unhJ4htUad

SpQvQpxTXsqVSr7COIqQapxc5umfk2OwHEOLxFfPMlyqpQySj7lNvlcpQjZJqErTbqb6fDduXdU/

Etx8N9Kkt9P13WVbzXDx/v2YDcN255o5WTAJy2cEZ+YkHI6eIOHuE8ry3D0uJMzeMw+bVIVKMKFa

tXrJU6ivUawM51I06MqkXUqaQi2vaPmnI68iocc5hDEY7KMrcVCLjNKkuZuL5WownTVS/o2+vmcv

D8SfhBoVxcJp+t/avJVQuwzyxSMAR5RI8zdgsVJyw3AjOBiuXB4Lwk4Yx2JpZdVzBOpClKpi6dDM

8fQqz9mpxjCpetTkqaqO7hOUFPmTlzxfL71TgbxJzelRnjcqdD2stVL2NOpCMnzc+vs7XUU7Ss9V

d3au7Vf2h/CcWnGbRYG1S93Kk1sBNB5GGIyJGTDEjkbc/dIIzWua8UcIYPLlWyl1sdm0px9nhcRh

cZgaMqbqe9OWKq0pRhyU3KSUIynUnywtBScorAeC3EVTG+zzWqsDhHCcoYiTpVfatq6vTjPRKVtW

09Wt9DC1T4zeHtb0uSMWQt7qeFd2Dcsyu5G5GfyiDwmTnnHGBXZw1x7wRRwssZneGrYPNHTxEJYG

lTxmLhKp79OLhjKdHkcakY05KTUZLmtPWLPXy7wvznKcxp1VivrFCjVly3VHlqQS92UYufeT7331

6/PA1bW4L25m0i4lUMzuR+8d1V2LI21ZPn3k8MSSxbvhjX5Lg6ObzrZjnOWUcZgo4uvVrclCpzVZ

0q1adaFOHtYOeI9ipJKryOc7yUHJyqRP2qWXZVWwtGlmFGk5KEYrm5Iwc4xs1flVrWu10R0l74o8

SahZQWSG9S9jYCMgySo42bi8YUibcGG1oSNvoc9PWxnEmaVMiwuT4mnmFPNamJlzV4+1jisXh4ue

sYxUatPERajTrRtLmjL2sOVzlGn4mG4fyPB4qtiZ/VJ4WouaopckZwtPlUZuadNtr3lUT+Ja205o

7/xt8QoLdbW61q6towiJJaXMRiLIBjZkhJQDycn73HPGa5afF/F8YrIa+cZhh6VvZOjjVhcPKnGS

5lKtUxWGVaK5Xzc85upLeLnJpOsHwrwZVryxGHyvD1pucqsMTRn7Tlnq3JW56UpXk1L5y1ad+Qvd

fvTBDJDPOt3IxWUy3DupwSWKktwfvclixXGcN1+alw/VUlisZLD16OKnUlGqq9GrUdRPWVepzSUn

PWXMpTu/iak4xl9Lhsowvt60KtGjUw8YxnSVOjFcu8buPI1eXNqrb63lub3hrxx438P+ZLpl/IBK

55ZQcLgDYEIyDIw83zRtx6njPfludYjhnF1amVYtUZpSpSjrXw1W023Ugqmive14KM5q3Na2nj57

wnwrnPs6WOwkHyRvHlvrJ7vnvZumkouD5lF7/Fc9Pg+Pvji0jji+xwyMCVJ2xgyMrcuF2fKPLBB6

DOMYPNfSUvEvPOTlrTwNb3V7RyoOClzdXGCaTcW4tK7v791rE+BreDvCeIqyl9Zqwg+V6ud4ubty

NuT53KqpN7+eu/Q2/wC034ns1jjufCcV0WPzyLcqAcHI/hXg4Gevvn5s9q8Q8HVpXq8P5bVxC3rS

xuIp87e/7qGClZt2bfO3a6vqmvEr+AuQYmUnQ4iqUOvs5YaT1u/709tFeV2/O5JJ+1ZdEst34MZi

P4UuV39PvEYJ559fXmuvC8aYerpQ4Oy3Eyau5QzLFzlvdNv+zKrukt3tZ3erJh9HjDRUZYfiiMbp

vmnh5WfNq9XZb2e0WtujMaX9qneGeLwOkS5O0tdqTuPr5avzyTnA5zgDmvUwfF+EqzdvD/LsdOPv

2o5lj3KCk3Zvlyv+aLs3vy63dz1KX0fIxaVTi2VWT3UcPJJrRtXm4q/o5O26d2cVrH7S3jq62Loc

lvowxJndAbteTnAbbDt5B/jDAnOQa5sz4t4kxsKUcvy2rklKnJuTwdCnia025KUYqpi8DOEIx95W

9jOTXLaceU+pyzwM4Tw6k84hWzOTlF2jWWHenVRcqztZpu0Xvb3ltyf/AAv74sOGZ/E4DFiGItVA

Qn2Jz3OT746nFcdLPON8biIuGbZo5U5JSq1cPltKnTk1b94/7OUYvbRxct7prmZ9H/xB3w7hyqPD

7lHk0Trtua3u21rJ2Wja22siG5+N3xEu8Ne+JJpvvcCCOJTyPuAoCRnJOQOhwSa1r43j2u5wxObY

indKUZVYZfBzV7XXssFGX2dHazcWruTaetHwp4Kw3u4XIqNPq5e1q1Zap2lJxnK1+mrdt/tFgfFv

xxEv7rW51BI52qe/X5l7dST/ADwKdPCeIFOV6OdzqO6+B0Hrdu/7zAK6j70vdvZX7pPH/iHHCVR+

/lOHk9XvJeVk+dtt37yvJt7GjpnxH+Il9I8VprV5chYmleOCDzZGjJ4kBSMtHFvHM3Tr65rxcy4g

43y+pLD1c4xkqtWEqt8PHCVU6MGr1rU8I6sYNtKMnGCbSafLyyfDmHBPBWFgp4jK8Lh26kaaqVar

pRUk9YP2kuWVTkV/ZtfE3qmru/deI/HFwks15qWpAqiTCRoiFjiXk72Me3yieoHYnBOSa8nD43i7

iX3Xj8diMNTj7adecXToyUGpwmpwo0ueHNFc0eaSlHmTpzi5Qly4fJOE6dSFHC4DAtuTpyiqvNKp

UlraKjNzVRu9n1801eKTxz45WOIxa/NI6BzE/wAp8sr3ZSpPI45JGeOnNfT0sv49w84ujnM3ShFO

MnNKfIk2uZ1MFJqyvJ+/UsnfmetrjwjwlKc1PKKMYzf72ClJynfXRxldPVtqy39baK/Ez4qmMRv4

siMO0LhbQByO2JGbdx3JIOR3yK9qliPE2grYXP5XcVy8s8BLmUlf3ufJk3K1m5Sk2/5m00uJ8B+H

vtHJcOzdVylL38S3HR3b9nTja1um2vzMe61bXdRIkvdbuGum5dl+U47kiMIOh/U8ZwK8fMMB4i5v

O2dZzWeH5nJunVtNT11lHCUsLB3bs3Kp9pKV2epRy7KcHdYTKqUaEWuW/k01rLn3fXW+t73ZVXUd

T06RZbfxJeW04UQhfOlmj+bsIS2D97OcMfUdjx4PJ8+yeftMPxHiMKkuWKjHFSu4y+B05ValNqMt

FeDcW58v2zZ4HAYyMo1sjwlek5c9/ZwpytfT97ypt3S2tdu+rem/Fr3jJ41kfxWY1V8DfGjE5+8c

7OTzlsrx15617tDM/E2pFV48SyhJ2UHJU3F2+F8zy7Z2V24tt30ba5vHq5PwypyhHhyMpTXvWq1N

WnfdtO+qvZ69N2a1/beI/EFjJG3jZ75ZI/kSFkgZXf5mBMDrIgJHrjG44xwfSxNbxR4goTo5lxks

RhYxi1Cm1GpUcnd0qssLhsPOC5otTtWqKdPScVzOJ52Gr5Hk2MhUXC0cJKE3eVVSqxkvstKpGVOT

bbTtFvXVvc5SLwj44msbiyh16WKz3sNkuo3WGkOMlHxJIIyScjEIYHng7q8XL+H+PI4LE5PhcdSo

ZdOadbBRx1SFCqrucnTgsPzU4TbbqQThGq5Sc6c25X+kqcR8K0sVSxlXKKdTFKMHzQwNByjG2nMr

wjKdtFb2j3s2nd5tr4W8eeHopBBfGWCXJdZLo3X3QTugM8n7lgcMcQZJx83SvPeUcX5VTxGBwuGl

QpyTbq4LG0oU48q55xp0ZVoQjKq7qVT2SmpxSc4tQa6q/EXCOczg62EdOrTaUZwoex/xLERowftk

tveqvvy9T6B+E+t65NpE2nanMZ7m3DB1ZUAiUl1ViV2kjy8EMeuc7jkZ+o8Mcwz3MsfnuWZrOvic

uyynhoUY4hRliaVWrCtGtCVRfva8YqEKkKs3Uc+dv2s4TXJ+NeIuU5TTzKljMDS9lQrcri06knUl

pOSvNtfHdNJrRbXudVb+I1s7+exvr1pZnk2QxRpvUFifl3L0JJxgnB55HFdeKxeG4dxlWOJzeUXP

EclLCLDSq3lXnNqCnFX5vebTk5acy0SkfO4jIZYjBU8ZhcNGnSUearUk3Tly2Tvq9eu11r/Ne2gL

3Uo7qeO7jka1fHlTeXkLuDFR8oyck4YD6AnIFdscZjsLmXsp4etWy+ryzWYJS5YTbcopwUXduXKu

Vu226jZ8n1XBToUpUKlOOIjJ+0puortXSb7O3e776Xs/nz4o2fifStSh+zX900M80UybS6rgbSRk

NhjjBUMSflOeAcfN+Jcc/wCHsfl+Y/25mP1HNsNKpTWGqV8NSw2JwrShSqulJU5urTbnTp1Obm9l

V0lGF1+0cA4nIcxwVX22Dw0atKnVpT5nCckr2u+bVJve3Vp2i9/RfDF02paVbTXlwJ7kKVkRsA4G

Rz2bjt356ENX2nAWbYriXhT69jM5lLH4SVanVhOjTu6lKtKMZtRcYOdWnad1FP37xiublPieIMOs

vzLEU8NR9jRvGcZKzUrpvTtrzeadrva/XyaHiHzcbiULn0yCcjnk9sHHIxwDXr1MxThGrWpvEzjd

WXNHmbdrtRTdrJL4ZPRcrasz5uGbt1fZty3UEr2d7PV2bu+snd631t7xW0e10+TzcRKNv39wJJOT

k9OTnPJO4fN161OHmvaclFf7TLmc4SVnFSb5VeS5b231Tur9Yye2Z4jG0+TmqO8vhSultp9rV7ea

Xk7Klqeh6VfXUplt08zgoQSAp/IcnqzAZOSf4qM8yLBZhhVPPcLSxOCi76q7jJSk1dU1zP3rXdnF

tbu/KdWBzjMMHh4unWkoPSSavzXffbq78z6mbq2mS21mBpaRWepD5I7rOVXkckO23OfQHkg/NinK

inklanllGll+d1abpZRj6kYuNOWseaSqKdON3r+9vq+Z05Rbv25djo4rEt4+VTEYK/NPDpO7vzdY

+9ZOStJS1V0u78K8QfCSS7vP7bv9XTzHm86/mMyh5DJJvl2eWSnmcBsYA3cZAzX5xieAONssnDG4

zMstr0MdWdTN8dh8xp06uFjOspznK8m68pxbnCmowhCqoQUfZx54/rmTeI8cPhf7LwuWVOSNL2WF

pKnNxhyxcIKftIxqcr6uzdtVuYmpeFfB2k3qWdxrUrNLEjF7oebJFvkyUkMA8qLjLHzjlvP4IXPn

d7zDJsBmbyjEZ5UxVCFON61enz+xnUvOdGVShBUvaSanKbrTc4xq/FGLi6nq4HiHiTMcLLFUcrgl

TqySjRfs41XGDXPD2r9pO17/ALq6TpdW06VK08M6ff63b6XoWtSO8rhm3O8bNGCDJ5EhPk7yrc+h

+8S2K4pxWeZ7SpZXxC6NClH366qyc5KpKKn7GmpKMtdNb8ml+ZJJ9eIz3G4TKq+Y5vlcIRpRsuWK

nabT5PbrljU5Lru7W2aO18U/C7UbOykFpcXd80lvm6eaYkRjALGNYeSOXyQM/LnB6jfizhDivh+K

zCMsTxJlVOlKpmdOrN81OMuWalTpUqsKkoP35Pl55Q6wdpSPlcg4/wAHi8XCWJoYfCqFZKgqdNJz

t8Km6u0nbZ+61ppLfw5/AnjCSOW3js7iS3LAiZYDuUnkEyeYzZj+9+OeK+Ow3HmIxtOOHwSlU9mn

y0MJhqmIq0ko3SU4QqVLqMJNSbT+O/u2S/V6fF/DdOVOvUxdGnWcG3SdVNPq1blUfevy62+b3sWv

wy8aoA8MCxq5CGGWQRSnlem+YMsec/w98/Z+CT95lPEHF8o0/quVckcROEGq9OeHqKnFx5qs44mo

pQV5pSg4uXxTjRlBPmyrcd8LzbVSu5uN5+0pwlUhrfdQi05O3lqv4rlocD4j0/WNNuvIe2YTCbZO

HBJ+baQ2RzjzTnjqMkDGa/UMoxeAw06dHF1Izq1Gp1Yp8/JOUeaCqcqaX7ybjG9veV4uXvJelH2O

Z4enWy+vGVGsnKUbqySU5cyu/eel2rvST1d7rkTNc206zRE+aB92QmQnORzGOvPGc9+ua+wqVKmL

pTSikmvcc01bWTTs1dW6R1cr2tds44UVhsRG8fhve7td6vml1Tdn1V7b/EereFvGvhiG3kj1cyac

5QwS/bTbp9pk3nElvJKj+QBj/XZB5HBYgV88qlDDOrTxlOdFy92Up8r9rKcm+aMmpcl58r5pXvpJ

tuTZlm+VZni5Qr4CcKlq3tIQvKEqUUr2nCNWHt1JpqMVKzaV4pbddqkHwbi077dL4ge5uJI4x/Z6

OftXnI0f+j48qI/IM5XiGfp+/ByeujPJcIoVniqsqkkmqEZKVTm2UFGNJarryyUZa/GtTwadXj/E

YmWDxGTYbD4ZSknjK7h7B0pc8vaxl7abfPeN0n7SN1dU4txfiWqXVk13dNp1qBZgK9ukwO8IFDEv

KnODnPOTjqARx9bgsfCrTitYwfM052T3vaVu3VpXbte92eTm2XqnVTtGc2/3ns03Hmsr2dk+VSck

rt3Vr63OSGrFd5eNFd8uUX688YHzdMdcjjNemsVSbSc1d6Oz/wC3t2vm+tvPQ4qmWU4pe9KUn0im

0nvvdu1uurvrqZ114gv1mItXWE7P3myLGfr1P69Tk980p05NtSTavf3nfXXdv8OmmxEcLiYpt4N1

Ya3a9x21d79/k3ta12zMttb1m1minsb0xtE2/wA5SJNmTnOzHf35/rcXgo3tWgm3/NFp9W9ZX6u+

l31MpYSo17uHqKT7KW6vZX1Sad3t2tc871/4jeIpdYtZtekdJrbeiq8EUYkSPnJjyORnODnsdwBF

eZWxuBhWtVrU1yXvpHZpvW8ut3qrXl0ukVRynMKzjGGFnyzavo3ZTaT72Vm23rq7b6nuP7OPjOTx

f4ju4dQt5ZLS3WS6ltLYzeX9kWWSOIHJyf8AUziCUc7SM8gZ/Os+zJyzWMY0Jzw6hXr8tOT5qkaS

oc0ORapqNdu85aSmlyqSTP0HH8PLJuF6uMwzpYXEV5UsPTqVZRcFOq25JRmlzaxvJXvZy11Z7h8V

tat/Gum33g+0Y6Uug2D6lbi7t0Q7pBEIPLfAIjMuWeXiWczDGDNivy/MOI8RmtWgp4eeGweVSxOI

9niIqNWrKDhTdFOnNqPtqeIlUo1Kl/rFSVN8qc0n0+H2V1eGMdheJcV/woTzjF08FWeGrzkrQdR1

eaOt58j92n8FKNP3v4R5f8J9H8Pa34m0jw7qN/HHftem6Gop5ZnvLOCCP/RbOKKOSOC5juBzNIPJ

m8/HytDi45sFgqua5nl+H/fYGjiMRNVKinUlyyUXXoUacZ0pRVWp7Gq1Oq5Rs4r3HGMKv3viHmec

5VkeYZxgsLOphlhZUVgpOXs8PXq1WpYiu6lWnOvQlRlH3Ifvafs7LSsvZc1+1T4M0b4ZeHDr2oXl

1Bpl14jt4YVVzJeRJI8jveDcQblpMkGFlxFKC24gGvr8l4czOnmyp4dKpPErGUsNSxV3KrTo0/aR

nOtZXUvd558sZQcnTk6jkpnF4Y8YU+MY1cBj1RofUsrhWxWK5OWgqqnCNPDcqUuRwTlaaUnOLUuX

Sxy/hzS/D2q2Hg9LLQL3TrjUr+E3X2zzZLhNNl82SS8uJ1M4BurfEsYywgHPytla8nFVOfFfUqlS

U8RGpCliatCpL2Ndc1KEp4enVSUVCTlzuFN04qjOV5xkpS+wrxq5VLO6sa2Bq4bB4KrVwqpwoQlL

GaKnRjGUuaU6daXLJVKrlJTSdrJR+gNI+IXgWyaW10/UFvxaStaRQWe0w/6ODHuld8xSxxmM/vfI

yecgjmuTH42eDUnTw2L5KathacIezoyjFL2UpzquzUklaXspVHGesHdt/m2Y8I8U4xRxGKwqwzrR

VarVrylKonUfNKnGML1KVRubvSdX3bK7v7q9e8G69pc93ptzYfZf7Punurie/gDoXuEilmNr5sfk

rm2KDzYyPJIPGACa8TL80zbEZ7gaUcLGhRxTxdXF4h0ZUp+0o4SviVQlVmqcL0vZwuo80KjnJwjy

JTPzjifKMfDD42jjFifrdBYejRwtVqahSnVhSWI5Ze0qfvud8k1y1FZ3XRd/pXi3w3rp1A/2haCC

2kaHdesqQuGOx/KM5bzI2yoIYZBb7vk+RXo4PH5ZxFLGYfHzhSw9CCqThjrYdV6NbmiqsPaS5lCd

uVwny1IylarTjFQjH4/MOHM8ylYNPBYl4ivH21sLFOrFrmqR9rGko8k7rVx+JbP2jrIw7nX/AAdZ

PdfYNJe8u2lba6QLLDcc9YA5yIy3P+0ckAKTnxsHxFkGBxuJhgcFiMbiHUUIezhzLFSgkn7KUpSf

s4x9pJXhD2iUnCEuZSn61HKeJsUsO8XmKwuG5E3GdSUalBf9PVT3qb9bK/M2/dR4XrvxF8WWmvC9

0bTYlshcoh0yW1gneWIp++2N5RMX2jyj5RAxFwR0JPqYTiXF4nGuvSfJR5ouGXypQnK0oKVRSksP

7b94oVJvklJUfsqXLKdT9Xyngvh/E5T9UzTHVJYiVGbeOp161GEKjqS9jzLn990PaWlq/a666xPI

tb+N/i7V5rqDSbU2dpHqEr3UMWW+zTA/Z5I5JIDF5b5jz5s3rcZr6KWZ4uNpTxNHDUZzeLwuHpqS

k3VhCal7SThPELfWEYVXzxTb5mfZ4Pw5yXLJYR1Y/wBo4mWEVOGJqyShVox5qqtGrzvWU1aKclpG

LTaTfz/4o+JnirW/E0mh6cfIjuLCOe7Fv/x+W8EZEUzeaR53mzzZn6Em3uAMjGT+hZQqmPoLE1ZQ

gq01T92Kc7wjzSlGrJXk3aTbjzSUrJO0ZOPyfEEa+CcaFSjKhhqTnZL3lKU2lZ8iei0SScUk1eL3

frHibxDB4P8AC8Go386X80NpZieO1H7zzZI4ceZ5hOfNPqceoGc19VUnTjSSm1Nu0LJK8pPbfdNr

m30s9dGfJYdVXPmqycY3b+00krNOzT1tfm31dvele/F/8NG2Oo6T/ZvhjTr/AEXxDDHLbQXFzJFc

zefHgSXOEB8qLzf37G4POSDisXl1LFRjDDSlRqyjenJN686Um4zUZKN3LVttKV5JvluvTr5zh8Hp

XjTxMFo6VSHNTTs1f2crXdm027316WcvlLxF8S/i/P4k+12eoh7xreRXtLaOH+y794zIJPtNtdSi

COU48+eb/RyTxkHIr2uHuE8Dl85qlT5sRVqSxE6tSpGVX35QlU5pKMIPmaaftVKSk+dT5pKT+I4k

46xdT93RpvkhBQjGPNGMUovkSjZ2SS0u310Suj4v8YfEe61+/wDC+m+I7eNtNtddntJLa2j8uXCs

8VzJLJKZPOiBPPnZg27iBkZr9gyHJqdFS5JrkpYen7y5b8lSVGSXPq1J6Ncsrqz/AJmfzhxLxBis

Vj5RqqpGU5NW95vVO17JXVr+9fV2ezTI9M8U69b6xq1xGlzd2ui20k+jazbZSPRR5mLW7m8rH2vP

7iCEtnyO3Ga78ZRw/s1GMozqKTioqSbV5Kzi1FqLv7t5Tu9eW+xyZXDHU68JQpO7eul2m5Xbu9vN

6apNtX5j6P8AhH8avilB4iTxzZxXutt4XsBfarbvHLeW8dq2YY9Svo5JhFBE2TN59vjABYf6Nivz

XPctoUqylCv/ALTOtzUatXnlSjKMVCUOWCvJqc4pxqOEedpOzUoL+mOC8Tiq+GeGxGHtSqQlSmkm

uaMouMlzJJ7Ozatq37ya5l7d8SP2n/iv4yi07wvNY6ZbaP4mu5NGZbXTEudTnj1EJ9mtobqOdgLj

zTCMiHLEn7P83NfLYXCUsbRxtStjHVrYKk8SqdKEaUZKFTmqQqKdKdScLRfJ7OVOfM3zKKm4v7fF

Ro4XDVfqNCSqVEnNc05JWUknao5Ri/eu5RXve6221c851DU/GWmeK9avtbSY6l4ZtNLtZLsW8VtZ

2lmkflReZYxgwy9SRcdLj/j5PIfP0WGpUakVKnNOpRjThe0WklDVNJWlHXmSTb3ktZKL/E86lmjx

EpOnOKlJu0tXZXve3Nt239D0bwj4o1SOzufFB8RT3Ml7dRW02ovcSxxslvkRW3BhEUEP/PHPGcZP

OfVlg8POKq83NzP3nJtpKN7JJ25Yq+2z6+80efDMalNcsm7rV7tpvZfe3tfXXq72b74najDK0UkB

kjlSQifYTuj8399JbdcSw/8ATc8DGDySO7DUKMWraLdrv7zu1dtNp6czdtru178GMryxLfo7vT7W

l0+u3S15b+9qdJp+uJqscf73c8kmYt8nmERnH73nkHPb88/er1YyoqN/iaUlHV22fld2fbstdDhn

QhTd3zOyTa11drtXa1TTv80u51llKbaVdsJkHThSeuD+7PTP1OT0GK4MRWpRlaL5pN7bbXctdW3d

ru78r3Omhh5VdIrT0e+rbv8AfdN+bN1dSKRyyS2kkMvHlhpPzIPbrgHB65Oc4rlVejFWalo9Lybe

7SbbS0/G21umrwU4puMW/wAdr7W9NdOoy3uLxpG2x7kY/vBjOcf9NOnPIPQ5PfPOdTE4d6668zab

S6S0sn71tbJttJWb3tphMqnWle0m13Xlo9Oujvd3vzbN3NOOKR/kdWR9/wDEc++QT2+vv7VyPG0V

b3r9NNtXJ+nS766ruepPKqtJ2hRk9mmk99u/poTvdNEIbWaZ2lg/6aZA6nOTnOepB79/TN4mlOOl

SLtsnu3bdWd2pX6t933Nngedc1ak46N6pptpv9Elu7d1qaNvc2067PNiXZJy8xJikByQPNIz9ffj

g9cqeIqNN3UWruUpaX3lfp1d9b31W10bUcBQbc6kkpLZWSvffX169fPp6PoOu6LYJb22ralokEEr

IUa5ki85Jsnk5zgc5hyd2R7lT81mlWt1klF2bbbi+ZX93TVXdlG19X8N9T9F4XeGjGUZ8k3GN4Rn

GPvTV+XWWiTfxPdpO1tWeuw+JPhdPEE0u4025ulEP2pFuYG3O2cGPCEtID83k5zB2GeT8JmP1TEU

q2KpzftKWsk6k4xm03zOF47pJ3imnB3bs+Y+hpZbxDiKrlU9jOjKUvZulCjOSUUnFVVCbly9FO16

m6cL69tN4X8IpZfaVO+eaNHjRbneoLxf6sosY8rgdpeuT15PiYjF4fDRnSnUre3ven+/nK87N8rj

vZu9uaprytv3k1Pw6ebZ1UxLoSoUVSpynGo5YSEZ6TS5+aT9/wBPZ/Z3vc5u78N6YltJYQoJpQr3

K/aZdxhlkx+92x/vYvN+p44HK1tQzDNGqlF1nKfJOa9pOKULylZyjSvOCcWmuayv0Uk0evDFyrzp

1cTQpRouryNQouPtH9pRnN2fLfZNXb66oytN8K21ne2lzqFw509p0+2xiQx4SNPM/wCWfDc5OSVP

HTmueo63tKVTHYupPDOpbEx5nGy9nKomuVRlZqHMry0Td1yyu/Sq5nCOGxVDLMNCnjVSf1eVvaNy

c+S9p9V71/ilfrfV9f4n8HWeqaNMdNt4mhdZI4GZ4wTPcR/I0Gzyz5vuDkHp7rG1qmAw9SeW3akp

eyfMlz1ZRXs1G04KUr8nNFu0tE7u6l83lucN4xYfOHzuylWj7OUpU4QlacpOftHCMbtrld/N208E

8QfCjWdG1G2vNLuvs9zaRwTzFRIXUu3mNIbkkgxRj9zyv+vJPrjnr4jG4qtQliKsI1KcKdWpy8zl

BTi5Skqkt6UXywvaMudcyvdyp/b5Nm+VYijL6tJwpzqVaUI1uWXteWTjyuK15pRfN7NxcXS95tt2

OY1i++JPmrM0t+JrKNC0odkiMbZLSyCKY+aeAPP4uOh4zmuWvRw+Kk5V8biKUqST5+apSh8Tak3T

nBy0bg6rcZTVnJy0b9SEcHRpzjRweDqU6kpNwhCnNOTTbio2k4xteTjZRT5uVRu7wHx58QJbZVGq

lwoKOqIIpCM58vzPPIJz/FjqQScA17GHwWFxVOH/AAsSnB+5Llbptw9nouaNZyTi3K0m03Pr1Xg1

amBw9RzjlFF1ObmvKle87v3mpRkrXeqta1+lzRh8ReNSgmju9Ruo54gsiubmWBUI/wBQ/kyfvYvQ

/M3cnhTXoYfJsueNp1YY/ETg4qE4TxVWVNx2cXBVHCUZL+Zc1kry0ijkr4qrDDSkstwqnGUqlOaw

dFThNbTjJU+aMt3dNN6u92eVa3pOtX13JeTyXcgXOd8swcfkPOBi9xwBkntX7TlFLLKOFjyTVlHp

Jt25dd3dyTb16X6O5+CcQf2vjcbVlyVEnKTlo7bvonFK6fX1OQa2v4JFUlwhO/dJJ5meR/z0zz1x

zkHHUV9Dha2EqR0a92zsrKSi7vrveze73bd3c+NqYXEUKl535ve6vlk2rP11drNe/su5ct9PuJfN

uJrgqpITzJMnzI4+SW4OS27OewOOtJ4mjCUmpXu7PfVrpfbT5797mVWhOrBtpq3M+vM2n6t773XS

8ut3xWkSyszpnOdgzkA8cjr1GenueatVdG7Xv9qL2vfW9rXtte2+l9W4jTcd6Tktt1/feze70en3

7p7Nu0tmyyCbY3MnXEaIOw446Hr19zWFSpK7TVvV3W6fnrrr9qzcne+nXTUnryuV3vv8TaWt725r

t+9q0k3Zyv0GnPb3zR2KOjXE7CJk5ckvzx755z2xnqOPPxWIlRjzR5mlbZ2veL1vo7NtXezurHuY

PJHjppPZtN3kk9Pko6q+yvq7PVM7S6+GlvFoM901zM80WJvtUP8Aq0OM+XJHICP3ZOf4eMjnIrxJ

8RYrDtxldtNpys3a6aas38KVmrx1jLe+h9FU4Apype0lJbObVle/K27LSTasnqrvRNJJM4e105LW

VZS4kVOCmMvJz/Pjtzz15Ir0vrVDEazXM5WlJSv7za21303fbofOQw/1Ob9nFx5G1fbVXX/B276I

2x4gVAkFrql9FhtksSXF1GPkAJj/AHcuevrg7e+cV4eOyXA4xq/NG7k1bmunukrLVvXTmTavbqfV

4DiTMcNCKpztFd7PS7e8np0UW9k0veuk+gj8R60+3ydXu2Upy7XVzITj/nl+9PIA9skZGck14WI4

SwTqp+2qLlb1VWrZ76pqS3dlbRfE5czVz6HCcZYyScZYWnOWt3KFN8z3b+GT1Xr2bKN7r/jRkkVN

avCroUjQXt65dGzkSx+bnI49T0Oc5rmxvCeCrQ9n9dxML3+HFYlczvJNziqsHySV9HK2qWr29HD8

WV4TVSWXYZ8rbUnh8O5JK65r+ybja29r35pXve+Zbaz8RVKXJ8R6rvik3QxtfT4PPU/vck9e5yM5

bk54XwRhXKnUWbY6LitI/Wa7V05vW1W7+03712t7pO+9PiuNSEozyrBzjLSX+y0ndtaf8uWmrNNX

1Wtm9jXi8YfEzYLmDWb3z4pJUUTbm+VOv7uSWbzouhB+YjkZwDVYvKcPgKcXDMK05xbjecpTbejh

zKVSd0mr8uivdaas9PCYmGOjKKy6goTV3FYanFXs9uWnF8z6SSTd+bzMK08S/E3Rb2XX4ry8R9+6

5uL0XFzbFZJc5lhkmWCSIAnlGyOMHg7vGo5JCFZYyjjnCrJylUnUnUqRn7STm7pVVHlha2t+VJJP

v6NfFV6tD6tisohWw1l7lox0iuVOnGEbwls04NSWtpdVrXnxp+I1xYX2myy6bKbmGRI7qCzeBozL

kk7zcNn1ySMNzk9K9eGRxxVKtTrYujUclJ89OChNXlJ3bb3035uzep4v1rAYWuq1PJJQqw1i/bVZ

KMkmoycZNpuLtJNxvvrfbxrVNZ8T3zb9R1K/mjePy5IWe58hI+ufJ/1I4PXrx7V9pw9w3kVGMYzr

06j5Iqd5NptKSvaTdraWVk5NuVz5DPOIM5k5tKoldtW0bV2/uvuknfvdsxZZb9kP+m3hVv8Ap5l/

fen7rt3HGK+hlw/lPNo4q+rgpJq7utb6v39ddeml9Pj4cR5xGT55z1e1paPrvKTvptbv1IBbSuWW

YyyNNnDv5kn6nnPPcEcjI7V3YTBUsHd6Jt3votU3rqk930e97WPHzDH5hiU7yqaqV01be2tm2n/M

922rvoWBo98pzHG0TEtgrIV6569eeM7j15Occn1Z1YT6xVtXtqvsuzu9lq0/ev5s8ZYTEzcpSc9W

3KydnLW7su+17O9/Nt37XTmR2Ny27HPlyZ356/dOfUHn6+ucKuIgryc483X3tb9Xdb7vq229ne5E

sNCa+CW77u+uqTtyrXfq7Jdi28MKMoUCJmOR65OQfwJ5B9fvc5NEcRB2lzRV9Xd7JNrtfz1XpdnL

PLm37sJpvROz1dn11d7N2s1pzard7NtZxxzrnc3yFt8nMfrnt065xgEZrGviuaXvOyevM3pvJvW6

Sv8APXd2bNcJllTXni1ZPu33trfddbX/AF2fLvPJZYSLhfWP+DkZ47/4c9OT5mJxVKMdakfJc3M1

eS103bd3dq97avr7+FyfETt7Om5Xas9ddbvdPWSsrJbtrZj7CbVdL86e0jcyyp5cnlx/aFzwT5vG

e/PPI7cnPmzr4PGNRVaF1pLln5Svqr2batrta2uy+mwmX4nCNSlQldX3i9H06XWj3vd30k7Jq/b+

KfFoLqkzxOeiJAf3mfy7+v8AUVj9Ww8NVXjZ6uzaa0k1f35OyaSej3fmes5V5aKk01d6xad7tv1d

+/TddHlX+u+IJ9rXGoXOVdpNriTzPMOJc85PpyMY9sEm6dDDppTrRdr6c1npsr2u3Zy6tye97s4q

9Wvyy5qMlb7Uk9vVvm62X56spN4x16Dan2viKVApI7JyeehyBnOeuPeu/wCp5ZON5auTtdOV1dN7

JuzTtJ2crp3tpY8FZrVw9R3ST5tG1e9ve2eq1um5dVfszoLj4qa1cMhW6vFnj/49mWQQBHj7SGLP

m4PtnGT15rzsRwzhqrbhpa7i4yd03zOy1va8rPS1+nf38LxljoqMZRfLLmUoyjGWzekrt811vdtt

763J7P4zeO7JWzqtpesU27ryzjurhPL7oG2Z4B6g/SvJqcI1VzctZ3l7vPOCqu92780u7Wrb973b

JNWPZ/1vU4pVcHRaXNKXJeinfWTl7JQ53ZaOSbRfg+P3jR5ltfI0lpHk2b5rJ/n8vt5X239SPQZ4

rNcI16VN+0lCUmlyy9krXjL4lHmb+0nZtJ9pK97p8ZZdUaUMFaVnqq1VNOV2+V82vnr56312Ln41

eKpwpjsdNikztkQ2ro4Plk+Z5hnIkzL1K/8AHucnkAVlT4RoVKjlKUIyjq2nFN6KWrUo81nGyv8A

BeW5q+K6UI+5g5cusbOtKSXM0ko8zlFX5kmlGzTs+Y5lfiX4hDK13LYOWk3lXtPLfAz/AKvEo47Z

HHp1592nktSEY2s7NWSi7prrGy3W/T8bnxOOzpyqyk6Sjdt6+63eUr+9fXV6+Zu2fxP1Jxm4stPu

LX959yziinfnGI5Rjb16jHT1JNRVws6NlJPlem++/mne9rPazto9phjVUjf6sntfXR31/rV9NWVr

jx7DctElvpoRF+REm2O/mHniPuc8nuRyS2Sal0K8G1rqrv4W95aJLvZ3V9brUdPEQlUScOur5bd7

+mqbW2ru+53ej+J/DVxAItV0TzpGzvRynl9cdTETjqW4zkjPSuLEVMTyt2lo5NpSgpfabSe+u+/f

bU+vwkMHOmueEOZqPvOLk79ea7vd3vfffUuzab4F1SFtugXkYnf53+1gD8fLj9Oxzz1z38aWZKhO

7nWlK+qdSU05WTtyvrZbW0vf7Wukstwle7lQjyptfBq7uV9LO+r/AMS1d1axq6T8OfDd1NFPawXq

AgkpM4kR1PDD/VRdc8nk9wOeMcZxPWhyqDqNczUryfLZu0n73NdXbdutt7t28vF5Dl9TmTppJLmd

tLdXdW3dnfvvvoaeo/DWxto7mS1DwbdnlzTzy+WOf3n7o/73OSMDJ5raGec89LpuP2u9tfdUlrd9

V5b6v5nE5PgI8zi76vS+z8rrT5ddW+W7PKtb8Maok0TWBLRno4kA9T1IHHbB+8e/SvraGPdSnGSs

9Hr8Wqv1971el7qMux83iMroqWjvu/K6eujvqtGvK0nrcc1tq0DRxz5lkReSqAdTnvu/XJ4yCOld

cMem/fakrPVarR6aJXvyvVvre+u3JUy/n2urbJdWvN20019b210jstcvLCQstnBdkfJIHj3kt0yh

mOPN3evrnjArnxNd1ZNRd1a213ezXutu+vfRt+Umn14V/VXFNc1pO7dnqtev2d9fvtqd7aeO/Dz6

e4v9LeC5C7BK/lvs/d5MpIOT9efXrzXiRwVlKT5tpe7zWX2mtW0tfybfV2+1pZnl86bjKEXolZxf

xdNbp2S1726q7vysvxEgt5/NtdNLsXPlpdZePngDgkYx1yf8K5q2Dmk+Rc15S5dW/wCbdaXvbTR6

yV022nvl+a5dhavNLl01ty8yV3rKz16ScfNvXY7XTvjFo6xZl0W6tgnlh/L+zSmS5kx5hjjDL5XP

LZzzznrXyOPyrG2knhpShZNXdO7lKTu4tN2smmm/dVrxelz7rAZll+PjeeMjSlypJPblV7XSs2k3

1bej11udoPiboMEUUltYzym6iZ1lRI0BiPruxz5oHc59AoJHkQwuJwt/ZYOpJVIyUqknGzTU5yk9

H7zk7Jq8nZSbTlZdFaGFnJe0zem4RacYwcp3d2m5SnOGvK7Pdtq+vMTxeOftA3xaRcxoGQGR0ALx

keZnu/EJwRxntzXLi69TBYec6dD9xHmc6kpNqzvK8lJ7Wlq2k73tK12aQp4RpKWL5ui96Ol1a91P

fmXNv1u2zag8TPMQ1volw8br+8KxSvg85GShJP8AFk8+/evzmvx1kWErylCCdS7U1KTu3HSW6V5X

ertytKasvdbTwlK2uNqe61yycY79PhqtPRWaVmrtvrbSk8T3sYZ/7GvGVVyd8RTjIyf9X349ck9R

3Hx9k8o81DmrNJdJpO7alZqDXu88dbK8XspW58lleCa1xsYNu973TabdruUNfV62s92XLLxBJqUf

mQ6PfICSjCRdx6/OY/LyDHyerYOOOeT6OH4mpY+DnhqGJUElzOpSu5ayUnTcJyTimvelzKzTTjFx

97CeXUaMryzHCz1bUk+TW94qaqXbm901pd9ri3ut6bakI9nexXSjzHiER85yONw/eHgckkkAYyeu

a6o5tgKlWMadHEQrK7ndTi9pu7Tk0/tu8b6d43MJwlRjOdbHYapTd+RKXPpfZLlte8lu9E9ytoV3

4k1+9uFs7C+ms+UJW0kfb1JbzOYjk8jPb5snv6axThzPkk4qLbtBySXvNpayTTaW6001Vnf4POcz

g6ko0nGEE+W8moWtdK7lZXb0bdm3rZat+teHPDXirSZvt721+I50CACG6lLkHIPl7WEnk8Hnn37H

4zO+MKNB+3pUcdNtyhHkwGKm5TcoqclTpwcpJW2Vo2973lHlPEljMqrRqUa+MwalFKbjLE01aTTS

5pNtU9mk3Jt8027PU9j03S769iK32nXSSxr5rvPHIiSDOY+dpJOOmPlB4PPNeTDi7FTpycstx7qw

g61qlCvBTvaVOK9z352k4uz5I35ZSupM+Ux+ZYXC1faYTG4edKrL2cY0pwnOm7u7SfqvV7XS1p6l

4flSxvb0acm0253gRYdjjjYSBL0Hc5/3a5su4zzjHYKvnlfKcRk3sISmqFeE6lS0U4+7G0ZOWsWo

yXN7zi02na8HmuGq4rD4WWK9+U2ubm3jbVVHfl77N6+9e1meYab8OpL2zvJ5tMFzFl/s7xRSRIhk

PmycRs+SfU9eOuRj6TIuOs3x2HWLq051KE5L2dTDxlVTUpSd4qLctFbnjKEPe0s1dL2cbjcDhqsa

LxlJVJv4JyjCSTfLZtu3xer0fM1o3yWneEILe6cT2zq0b+XIQwj/AHWM+b5YbPWIDng9Ce9fX/2s

6iVSMqnM0ua7lF3s229Zy5oylzO7d78zT1u52kndq7s72k27PrtdP3rtN7vXU9bt9M8PSW1nEAjO

yJB51wEVN4BUeYPzyCpOMZz38/MswqVoxp03UU5vkblPljGTu5NqXvNaaSu7WXZ35lLGU3VmowlC

F5wUeedVpK+nd6Jv/t52d3f2Twx4B0G3t45baGzvIpws/nPHBIcuedgiBjEXOeTn5uvY/OYTg543

FOrDE/XYTn7ScasIznSc3/y7kmk4Plv5eSba/PM74szWdWdOrKthJwbp+xpupSXuL4pp2k6l+r63

v3ejrfww8P38crPY2RdopAUWPGS/Bk2L8ol68k99wJIJPbifD2NSdSpQxjoV/ZTfs4SqRc5fHKUl

GqoxnFxs6krte/qrtvgy/jfM6Tp06tetVpqcZt12qsVy2fJz1PfdNt3vdSvHW2y/PD40/Ay90yab

WNBto5IhNKZILY/Ikm/zfOBJzH5xP+owRuzycGu/gLjXMOHMV9Rzjlq0pV50I8lX2qhaUvfnKblU

hKs1f2Ku4uUYKUtLfreGx2FzqhGdCU6eJ9nGc6E48rlq4ycGl+8UGrc+i2bsj4/1PTNQgma1kt3W

Zc/u1xl+hIzg5PPXPXviv6ZwWc5fiIRxNHGU486TdG8ZKUuXW0m99m3dta8yehxYjA4ubssO5rrK

7Tvuul/N9b2e9+bnrjSNSMzbrCXesaSOcj93Hk/vevf1x1zznJrsjmeXU5PmqRlu0udPSzlKerW2

61bbtdq7t588txEZt8kk9XJSi3d3tpe7b0co/wAyer6FJbC9aRWhjuGcyfKiJJJnnvHyeccZ5z1+

brrHNMsqX5q8WrfCpK28m5P3ru1+W7a933dOmssuryjFNNvpfW+rs/einut3utL3R3ekeGdXuzBb

tBO8jnKjbKJ5ODzHGB7e/YckE187ieLuHMPmkcrnmVB1ne2GVW8lKN5JqSle9uZ3cvsvVtXY8uzG

TV8O5xTvy6K19Nb3V2rvXmk7LXvQ1fRZ7G5kt5gyHyzJgofwydpHrkbsCtMNxbkFfMpZbSzCg626

o3tLWN0lNy5Xpa8feSVm7RvYrZTiVT5pYaTjfmc+Zvlla/dt3ejeql2eqOTfS33MXXy2Tn5068df

z9M8556mvqaVenUS53Ccd4qD5rp31fJ3sndy1e+q18h+2T96mlrbf3b72s1LXXa1uww2D7kaQoI8

n5B/B/20Pp16++auoqTtyQ5bp33d9ld3te2q0dtiatP2kW1aL6NbX81Zd1e19XfTZ2ZbJpMKqZb+

Ddz379z2HfOPycqaSWqb31kns7Nt33Ta6LfyTZCnUi7Wut9eVWvd7Ju6d+rsvkWDot65RVXcf9ZG

3EZ/Xoc45xnPr1Iq12veXu330SbetrJb99d3rqRONnp583NK7303bb+1onrrdmtp+hXdzL5dwoiZ

cvI6P5mIxnnJP+OBycc5xq4j2NNyqcrS89LXd9G7vrfW/J3smro+yc241dXJrrdXvfmVknaTu7Ja

2fR39N0f4d21zM8d1dSpG0X7vadmy4JJHmnMvfjGc9z05+Ur5/hoVKicLySk0+dqXN70opxbkm5N

X/mSfNZ209GGFr1LcvvQfvO75bpu7tG90rKTut/mr/SXw5+DGlCSxutWuCB5ao24yM8sneTYRxFI

B+4hIyLfqATX5VxBxljqK9jiq9OjKb5bKcJtRcm4tRglKpeKasnpG8lLSVvWdKOFw86sKftpQV1G

MrKU09W5O6Vru71bbsrNo+pbT4Y6BcBLaOKMKC3ziGNl4wRyY5vqTyAOCPX8qxlXGZ3iZ4Shnden

GbqurOnH4P7sbxqKTu37zbs4yTTkzx58VYnAqVSNChGzuouLnO977udP7rr0buy63wT0jYD5KuWO

du6GPnPceV055JJ4YDAxk+ZDw+zbBuVTDZ/mOJk3zqE8VyLmmtWlFReiekZLk5XZKLMX4jV23B0q

Nlo74bnbWmt+a/frvq3qeeah+zvDLMWgsYNvmyE7JGXqcZO6QYGc45GD8v1+bxOR+L2FnN4Oq8ZS

k5RhyYmhRmlzSvdV7pKUG7v2jt714x0T9ulx7k0oR9vT5JunFySTtJ7PRR00973VtumUP+GfbG3A

eeLy9x5zLIT3GeZB3OCemM5xxurCZd4q4erGpmWJnhYPmdvb08ROUnGTfNdxS35tHNJK2l7LVcaZ

XWly0sKpt7tSkr21Tty76Pq99G3qpYP2frWV3ntYI5MfKz42v1znmQ85+Yc9hgZq6+C8WK7Ty2vH

GpRs5OVDD1JNpe/aXtYvm/iNqUYqV3bSEXpLjvK8PeNTC+zm1p70nB631koLTpay1d27mlF+zvac

meySQMo/eOCSOfm5EowcH0yDnJ7Vpg8B4v1cQsPm+CUqMlFut9co3p2krRcKSg5cvK3zW92+k5Np

LlqeIuWPSFCm2m1ytyd9Le7eL+K9r3va/dshf4A6FDcDZFGcgbuATyT0Hb64GST68/bQyHjPKVTr

4fOKlVTfv0ak6E4x1alZpRm3Z7v45Ln9265R8b4XEU254CEbPmTjKcb63d9ZdHdpO2j6q5mXP7P2

gP5iiOIuw+Ulwjj7zcSAFjtI46dMZHGfcws+IqNBqeJoyrJuUJ1MRT1bvK1rqTdm9I6qau92jSPF

eEqRi54WpyvdxleOj7PXreV5K62ffmtQ/Z9sljmNupDIrNv87zPMby+Pkl/eevqOhyor08ux3FlK

s5V68a9JSb0nFRa8m/ea3traSWrvcr+28BX5Y070nN2tKMrJuX2muaG+nxPTRq9zyq9+HGlW8rQz

NMXg+UY/dyGQ84yMr7hgB+IPH2azGeNhGrOd3G1/ed+ZddE9U7q972um9ZJ9E6daCakrp68z63/w

6PR3T1ve65ncktfh3YSw+bHO6JHnLy/vDxjBPG7knPJ5znnpSXEFWa9jRTXK7TnppFq+zum9pX09

W7Wung5VeeUm9VJ3lvJu2t9FpqtebVvdkC+DbLdtaV5/nyn7zZ0PYcknpyTwfXANdMs4w2Hw9F02

pS5al73bk93eV9E/te9ZPeUbXMFgKTbTquzXvdVdO/T520t8z1dfhbqiaNHcJBbyRou5HaVJIskD

g8GTJxyeSMg4NfEYnirO4fXMRh6UalCDi1JyppWt7yvdOMW9G0ppO90uVpCq5ZGv9UeKUa6vePsp

pXUXrzcqT1b163315nm2Hwl1m+lj82yt4oOkqwOzts48vc4EY6Z6fUgV8/i+MuJqleNKhgHTjF88

uSSxKdtYyc0k4xV725JOel2rSNKtXKMNzOriYS6tcsue99muW907p3lb067N18FTCYGkkFqG+R97

+ZJ5fJJzwcYO71B9uTvPinPJ04Tx+FjhHmKklKVdc0fY6JKKhGV5q+kHJ+d074Qx2V15P2E6tZxf

NZU7XV9eWUr3101eqd7XJofgIJ4vNjkmmXcWLiTcT35YRcn1HPy855GZp8Q8bYjCyWDwVKWGg23V

p4hTcqblK81emm73V+Zwu33aiTUzfJKbdCs6sZS2U4KL72a5rq+12l3XdZF38A5I42IinZWOZC+C

B156Rc5xwPXOc8V4GN8RvEDAUZewyZV+R2m/bwjBwald89WMX7jurKVS8dVO/Ml1Ucy4dqWg63K5

c0r/ABau972lfe1720tbo3yN58BofPLRwXHl/wAUbBwuckno+eRjIJGM96+Y/wCI+Zv8UskxXxTv

z+0TfvaO/sJJ8yvzWejWkpXuuuFPJKv/AC/iru75r/J6Ntvba9uttbbmj/A61gil3QTASp91YUQE

knOZTiUk9SAcHPzDj5vRwvjPi8cpL+yMfSnJqNLnptU6knzR92TTl7jWuje8nqm3jVq5TRdlUjPu

1J3j8V31vdu+r1aVk769WvwQ0OJEYQXEMgXvKNm6TmTJMGTgknufoQK9J8d8S0Kd7VoOSTTlJ8nv

Scn/AMuoyV1yayu1Jaq0EnwrH5ZztRh7SN2tGuZJXcdpXd33d7q9+rdB8HNNjaGaLcxBz85DuwPb

/UccYzx6Mema4/8AXTivGQp1bz97mlVvdOMftKM1Bxc22o3ve022uayOpZplUHJPDTU4/C3OHKrP

Xm15neNrWkrtPZu8ekT4a2aQ7Y7dHJBVpZF+aUc58wgHdkc9T19iBlDOeMMRGf1fLndb1KmJSlLm

vrODTjG9tul0rztrouJMMqi5qVoXWluZpPVqMk/ed3d+fYoT/CNbkqTsRlOU2tJz6jn5Rn0PT+9m

uWtivFPll9Vhh6Ed4x9tGrN35+so0+Vytdpqbg5cvtJJwKXFGVrfDzkut5qLd9XrzNaPq732dtW6

GqfClNOtndLWe4WQBZNz/OeSC6RyBiSM9chsZzwSR11OI+LeH8KsXneXVMbFciqxp1FKXK0k5wjr

ObXxxjpdJdzXBZ5lWYVXSnKNFtXTveMddFOSuk9t9Nras5Vfh8x+VLWVhyOYikuSRzxM/JOeeOTx

Xl1PG/BNuFHI8XWacoSbUbqU5OMU+X2msnunaUmmnq7r05VcBTXuYqlFys2780Fe7vz27PXRx31a

0WtD4IvY2iWCCccoAd7L37lh249SR1JJyM6/iRnONrKGX5NiZcyjaVVVsPGHO5e7JzoRu4t+8k5N

pNxfMlzVTx2WUoylPFPlipXSUZXaTerV3r05rPXXqn6DY/DrUrmNSLMHOd/mEy/IQT5ZEmAQT1GQ

CB3wa9iON42x9CNSnkqbcud8+J5nHflpuM1GMrSgm73TVmpu9zxcTxll2DnOMa8k7JKy5XdP4m48

zfVLXXXVNpvRk+FlmbWQX9ttJ2+cWwvfPlrGJGOBk/Nzk57ZIeX5PxVmOFnU4gxU4zTdSapyjRjF

RqSlClBxqN8sYq0m+aU5bu93Lg/14nVxEVRlGrGS5YRUVO65XepKSpp3e9lJavm11v5DrXwssvtj

CGORoCzFZNrGTa3/ACxYkkkkhsrkYwCBy1cVLjbG8N414KWCxGJoxU7V+Zzm56yjRs03efvtyu0o

yvdJ6fa4LPcBiMPGeKw1L2tvegpOMVKTs5OXNflW+tr+8paqMnzV38HZLi3k8tZYY1jkKF5Cz7yf

MdjFgk8k4BzjOQ2c7vXwXibn+Mw9WvVyethsHCEmpVcXKeIvBKc74aNNVE+tpfvVJaJt6dkM64ej

OEZUIOpJpSVOdox5mkm6knJPWzukrp62ehzkngKa33LJBMwVcIxCg45znoc7ucHJJHY5Fc1Dxywl

J/usPioz1jNSdJ3a5vi5q1007XvGVneTTvY96D4fxEYtcrc020p6rrpZOzS63s1e6tcgn8CxpE+F

Yebhim7zDvP3uQP3QXPIHfK8kDPp/wDEYsDCHtZVYznUiqipw9+blNPmjJx5vZOHMt0+a0tE1YhY

XJ60nGEZRi225uyVtVzJte9fTpvr115mbwZqUB2wZYbANzRjy25J7TevcjPPQgqa6KfjfhotQVGU

m1d35FC7j7y99xmmn3Vr3s2mm6/sHJ6vvRxMYtN+5L2nMn3tGOzV1v6N2aVmy8M6s7SLIiROiK8M

u7zPNlz7/wCr9OAWPJ45FbU/FTKcxqShKEcPVtzc1SrTtOo5fBTbXvP3k7vlbblJJyhrvLLsNQ5X

9dhKN0m1GbcbK7co26WvzJy7d0dnHb6/Hpz2KjzQ3SQASv8AJyc8ARRHIx9evIr1cPxVlmIo/upx

qRqqcuaE1P3YS1k3ooR0vFc15KV97GsY4aE1U+sU3VjHljUneFudbWbanJNW+04ybd+p5/rGma/r

No9tPbvuVDDDJsiOyPzOf3fQ9cnPfNeplXiJkWWpL6w7wc4tNSlK8Jcs01aTbhfmk05pJ3fKlzHl

ZpkdfMYv2mIw/vLRqpBe7a9ua6UuaKs9W+u6duCuvhjrcsZjRTIhJ4KoPLPvk55P8XfAzkmvucL4

w8JShKNbMaUJU24zV/hlb/FFx97lTutZPXd2+Jq8Be9JqrSlJN6upTV3d2+0042d01bR7aDV+FOu

eRsa3jVVf7/yfvD68Ey9u57dORW1Xxi4fh/y8ptaJTdW0Wm58tpa35km00ndRTva7eMOAZyneVai

rXXKqlN+673taXe172u0teprWXwf1m/hk8+NIkHJhE8rSSdSSWXpj689egDVEPF7JZxlUUqfs4cz

b9tC+nxy5G9k3o3d2UXba/VDgrDUZqNfF0ouW+jmt2/eabWr2TfM9b9UOuPgvcxIofcCU2wQOnmC

S4HOfNPkmLkDHnc9B9p7ny63jrkiqRpxxEI1K8uSnTvfmqSv7vM0lFXfLerJXdouTk1f0KXBOU1e

a2MpSVOPNJ2u0m2rpX95u71jzO+uxiQ/B3UrmN3ljtolLlJF8263byRHkxiDH4jqf06sL4zYbFQd

SliIv95ODi5OMlOM3F88akIyTTWvRe89Xa+lTw+ypSUViKfNyOS5bctmnK97tNWtJ+9HfXbV8nwa

mRhsgkkY53+dGUSPHpGc8Hvnof7xr1qfixTjeEoNyk3rzJfzNte6ne9r+f2r7qPAGX2/jUHfZqVO

V/8At7XW91ddXqly68vcfCNImmDi4LTAF5bWN8KUPPlCWH/V/vckk5Iz16nsp+KuDlePNFt3b5Zd

Vzc0tY3t3bspfF1V9I+GlCT5kqXK+nNGV+ZPq5XTbfNeyc3deZzuo/Due0liihtLl9r/AOuI3yxE

cSHyuvQg9Tkdxu5ut4pYG6TxsNVK1p6w9xuV4XuuVcstbON3fa5yrw3oxf8Aud1q0+e11e/59762

Wltaep+Erm7khjXT5oVWPO6RJYzIB080Yz054zgZySSa7MN4m5VW5G8fSi6l3FTai29b6OSlJXav

yp3bWvfgx3h6oQSWCbTk2tXpLbfs211adujuYUfg/UoJ9zafKzh9kjvKHj2Ejnduyf5dRz39T/iJ

GRYeTdXM6Ctq3KUYpp8yXvcy0c7JN93fs/Hfh9WldPCyW7bt7z91y35H97b1au9zU/4QbWL1Xa3t

ysWPM8wrKVOM5/1Z5Ynrgnvg1y1/FrhSLm3mmGdo3v7RNp6/y1HdO2l7Lz7v/iG05WvQkno3eL09

XbVbdNH1fxFgfCLxTcxiKK3nhKyF42SzuRJ7HBi4/wB7qfbq3EvGfhiUnQrZlQlXk7wpqTc2tWrQ

jdNWbd90rqTs+YP+IZYi93JRi2mpSSSt7rkm5S5b9tbWfXVu7F8MfFUaxoLS5Dx4LyyRPBASc8/v

SeenTkHOMljXp0vE3J8TFzq1E4STcZXlBSjsnf7PNJWVlJtqybbkehHwpqVrKOKhFq905Rb15m7w

Um5L9bOSutR/AniqJkcWTPH5mXl3AIeeG4BP8OAcAjsMnNc8fEzJq8/fioLmjGM+Z8rTk1HW6dut

7u71tomX/wAQqzKmuWhOEpJtpJw9ppd3Scm3fayjtbbcz5rXVdKnXz7eVPnKF0XKSPIexOOvJHfp

gdDXtx4opYuPNgcTT5dpaw662tJ/PXR3bainY8mfA+aYWo4YjD1JO7vJx0bej2Td/JNXb1urHTaN

qltDL5d8rqzYMO8E+Wf+mmfTPJ4+nWsqvEFChfmq004q7V4rW93Z3j0Se70T1djqpcFYqo25UZJT

SafKtL3vdqF/k387anXTeG9Mvo2lWUee0Pyb8/J5nTovb65JOcnFcEuL4UW0qnNo1vfV69G+/u3e

jvZX1PQh4cVKq9+Lukmvd6SV9rrV6L7Wr6M5y98HXOnoJZoWnib7kzoY9nP48+Ux/h7c5FaU+N6V

7c65ea1tL6y96z5rStq1717pblrw75dPq/NZO7SfRPS/xO793pte/bk9TC2qxhbcqqPl5PLxEMc9

sevpuz6161Li+jKLaktXvzO32ne7v9pdXO99EclXga2iwza1e1r2eujXKnpu99WrasSC1tLqGPzB

+937yz/6ojPU88gep65yD1qq2fqpZwlduWqet+a9tnzLqra3Tva9xU+EaKXvULN6vu+tm3F73lrF

+8ra9BsvhbTb+7JjTLtjfu24MiDGY+pHfPA7H+6TFPPpwu05P3enWzlLTV3ve2liXwTham8Yw35b

Rd1LXe0otK9+6s7u1g/4VqLlJpEjiKjKJOvmF4HPP73j0yByf7xJxmpo8e4SipwqVYJx91vmcbTu

5PV8yS7Ra163badR8NKmJV5Ss7tfB0WitZq7tZ31emstHzc5rHwx1SBjKH8vcMp8m/zMA/u8Ak9g

QPX3BNezlvGOCxDc/aq7vu21rqrO+vXpe+y5b28HN/DethFJ0pN36Kne99Wr311eradtW76s4658

DalE5dpA6lPvyRtAU5yRyCefpk9c16/+s2GTTdWLWt2ny2upP+a6Vku17pW1PmJ8D10tYzvJu+k2

rq92tOXzXq7rq6CeENTaOXdAxVvu7ZCZPcAD/VDHrgEkjOevVDiLDySvNb83vSd1yu6vdu1/V3PO

nwjjIfYqJrT4bK+uz5eumr169dIG8HajCA1zB5MUzGGS5DByjDrkx9s+/J7nHGq4py33f3qd7pO6

2Xxa31V1rq/mjCfCmJheXs5X1esXs7v9b30XVK5XufCd2yYgQTRp0uZs25jJPQ9cnj6E9qp8UZfa

8a0L99bet9evqYS4cxHWjPXXaV2tdfg36apO/VX1WHw9PErRhRMhO53T6/8APXg9zyexJ9CKWfxx

DSvG28XGSWmrd9VrbV730u9U2Q4drNfwJ636NPd3fuxe/rcr3OhNvVICJJZR855Qp7k8gjPGe+Rx

mu2nnOHppt1lfW+tk9PN9rvvqru9xT4brO6VKou10+78tdlu35vcRPC1+0qu29o4gcRK3mc8nPm5

z+A7c5qpZ7lWv76Kd3e0rr83qrvVt7JO9mQuGce1d0Jry1v1v1+e/TZa30l8KapEqyRxCTevmSKm

C+e28kc5yQOnORkgZKln2VrX2tPo1d6WfM+kr63Wmztrbl1ifDGP39lJXaaune99bd+jvfbvdj38

P3ltMilZjuTzPM2fJHJ/y0hkznmLuT1zgAmlHPcrptt14L4rXfa7u9U/leyWuyuo/wBW8yb/AILb

1s7dbvV80V/Lvputdbt93pO23YxzP9pCcfIJI/MP1wc98clsnvzRPiPK+laEp9L82r33Tav633Tt

qiv9WMxk/wCDO2+197vo9W2tXe3M+uphzaFqBtf3sE3lqgkaR4yZCc8bunQnnjnOCTWtLPMPLX2k

VF6u9vdTvrtJXdr9r3lvcnE8O4yjBtRlrdfde/S/Rr0u72359bKWQrEIwoXOw8Z3ngYTJPQnp9T0

JPV9foVbv2sXa7bbinbXWWt7NxfV62b1uzy6OS42cpLlbSvLr0bu3da9ervdLdkkmk3TNhnhEf8A

FltkvXnp35+vJ5xml9foO7dWPNsnKSd9Hay1l5vpe19dRxyLEwlf2Mnbsm7rra6t0bjq3pfbfT03

T72yuJZII7iOYwlYZo/9Yn/TQ56/r/j5OMxNOfM5TjJ6Narvza3bWsUld/E31ufRYLB4mik/YzVr

NtReru77Ru31Wm+xqR2utzss9813Mok+7c3EkkfrnyxL3PPJwDj158uOIw9KP7xxne9m2t3Jq9m7

7WuttXfdnrfVcXVlFwhV5vnf/gb2ad+2h13h7VPFunpLHoV5dW0I+QwgSJGSf3mY/LAiJBycgjrj

knNfH5vhMFjXK1Wmr3T0i2316au6TavreV073PuMoeb4aEXy1XZap+83a17Xd201dydtN77nolr4

6+Irsw1GdjCsP8MZjkD5PlnzfNH7o5OMZ7gckZ4KXD+SpuU6lJ2tbltzN7S5pPSTvvy281u37f8A

bGbar2Ml29x9/K9tPx+8kXxh4ufbF/aV+0Lb94M1zsWR+mY/NEXB7887jzk1csnyiHNySi1J62lO

TT7215ftbNa63e7TzfM73dOokn/K/P1vfTfre+hvL4m8SxrG7yCUhfuRx45xng/5J6/XjlkuRydp

wi7Oy91/Febil7jd7T77W0fVf2tmL1lCo+a199pJtXuktW7PXVa9rX1+IvjCN0eS88jamxHhjxIs

eM/vPMPTk9O2OPXlr8O8O1W+bkXT3XJ30s05bPme3363OiOdZirrklu3pHTm968vV2Tule0k/wCY

nX4leNLhvJ/tHeOvnQQbJEzk5MsQEw/h7+nOcVyVshy2nK3tIWUvcaWujer67Nu19+rW2sc7zS1l

Gdne6atG3zunp162Vuhrah8QfGmnWtvf3IeexYR2s04gly8372U+Z5nbyQOw4OOO+OJ4cy6rDm5k

/e5ef53d3r0Xz2adm3vDOswT1g1a70ja2l23qr63v39Rtv8AEnxFqbMLcwpsIf8AewmTf5hPtxwO

SeTnFcMuGsHa/tEkrt+6pX1V9o9Vrv0eu1+j+269Rq8dVtfm01vu21p01WosvjrXbW3nkdYGaLny

0tw3mSEj91x9cggZ7nIzV08mwlFNN3t11XM+aS5bxTW6adnr11sKWc1aas4pXTTTve+uybvffR9d

NWYdp47165vYbe4ZLdLtxxBHseM9BmbnsD0xkk4HWr/s3B3SdOzlJNJXdnrfVu6VlHqk3vd2OJZ1

Xm37r1TWsXre/wAtNdU+1rWSOyTxcFj+zG5kdUPzrjMn0O/nA692781zVcswG8YLS9vekm9ZPW7c

Vy87vdXaXxXbb9ChmNZyScW9VdXTS37972u22+t1oa1r4juJYvLgeFN0e1JmJ808nvjBOBuJJ5/n

5Psp4arGTS5eZpLW75ZdNf5o97q9ua2kfqsLbE02pbSV7WsldXaSs1e7tbv06HluqfDme5ubm9W5

hkur65knmwftG2P1OSP3vrwSc/n9ZhM3lhKTUqlldPWTVtG/dV3e2yfvLS255WJ4Xp4upKbSbvfW

767/AArdb33aXdt0bPwxFp0ENu1i6srvJIWMTx+a/wDrSBmUHt+ZPet459Vm+VOVpKTVnKSWu7fM

0rr3kvLbcw/1ZoYdNpRej3Sa93qm4rbyvdtatIrTaJ5+AESJd5fYqqqA8n94OcD6f/Xrtp4/ETi3

zSS1b1aT5uZa3l73K1rZ+r1u+arQp0m4qMHfRqUI7p2XvWaT3kno3ddblgeGrOa32yyrE+Qd/mR/

J1BznM3U9D/Ot1Xqwi5Obve+kuV6tX21bd7O17/i+dPDu7lRT1alfq7e83to27u2rW97tPPTwhYx

Rzo5hufPQoswHzwHn98TnB45JPcc8Vgs6xdK6i6jilZa+urvJ2s+bs73t1OPEYLA15PmpR5pJ2bi

07311Vnv097V31uc3c/B+2vJfMW9WBtw+Xy89zgcnjjr1z0GM8exhOLMRSptSlJNacj5pON46a6v

W71vfbrFo+XxPBuEr1E1GEVdvTrforp2esve126aN01+CFsJN7Xxl3dUkj3xZznAA6j1IyeeTno3

xriKdZvnlyu/M9dX7zd22tneP4a6kT8PcPWivh2V1e2/m1f4Wnt5u9+ZXR8FbjChriKK1j+cfZ7f

pyf+WRJ8rODg5yOuTzXTHjWvKOjtHe9r83NJ3VrvlV73bvdrbdmsPDXL1q5Ru020k7p6vVuTTbfw

2VvzLX/CooW+eOdNynJmfzTgEn/WbSeST64OcdaJ8bz5bxbvrefMmoyvpvbmvzSeji03fW5u/DTL

rO7jrduyfW7961r6X+ST3jcqv8LPszxhL9LsbpNkRtj/AKz080EnPPOMdckdq5cVxrVUU+dt6WUb

31676X5r3tslqtWaU/DjL5fZjq90ub5vZapPfa3dkMvwoury5aWKdLKNfL22zpLH5meZT5pPbnHH

cDOc1yR43rJuTbj0Sbl9/wAVtul3va73edXwtwU7tWvfeMVHq+7S2et9dN2zKl+FD211utSy7X/d

+d88cn/bQ85I75x25wM+rS42U5rWW3NzSvJtN813eN9dF0evxO1jx8V4XU4SV2kr76J3fMktWkuV

PWV0t+mrin+Gt3BG093LCLkfwJ9yePP+qj7nnJz0IJJzXovi1u0nK+u6Vk0m9E+/NbbW+pzf8Q9o

wXSV09WnZt3tfXRvfddVuyuvw4vbpVkigmh2nPm+R5i9+5JI79Rg5b1Oaq8cTqLlT0tf4ZJX5WrN

NPfmab1slf3tb6UuAqSlzNR5u7S6N20fXq9bvo0rnX2Pwzgay3XDfaZSPlzJ5Eok83/lqY4jFFES

wyc9xxwa86pxVXqRcpOT3V1pdpSk17ra13bu21ro22evh+FcPS05Ia8tvdXVvW6XWKbs4paPudI3

w/tE0vVLXe4W90qezX7OJBcRyTReWZYgCWxFknGO/XORWuVcXVY1/Zzcknfffu7Xv6uz1u7bNSWa

8G4eeDm4qLfK9Y8r0akmtld6p6WV3ZPW5+U/7N2hXXw3/al1HwP4qyLjVDrenQxTjZb30skkt1bS

3MfEXlTQ2uf32MT4OBX32JxkMwy3DYqmpSlScsNiGtHCooRclK7k7SmuZJKVlUhdaO35plmQvL8x

nCcU4SmmlJrVOVnJp3tvbmUt131f6o6p4X0m5R4jA6kSeYrITFs3nH/LLHrye+eMbhX5xDOavO0+

b3ZTT1cXf3lurq/R3tZv0P0+rwzl+klBNtRk9OZe98TvLVWut+um9mc5deGLO0tWk8qQsuCoaUnO

Dz+PXvjjrzz6UM6qWWs7X5dXO9+bTaW1mk+z8jx8flOGgrRoq6u7rf8AW3wvTfXV6o59LiO2k8ho

HWPOwufljBJz1Oc98ZPX6HPoe2dRJ8z03s5dbXdtHvq/JvW9zxIxhSu+SKSdnaK06tXs16vvq7XN

++vdBuljKaagdYSswaOFHeToCk8XUdzkfXk1uo3t8V9FrJt76e9dJ9G363M6soWd1BN3S93TXXpG

/q1Z3d7p2MVobb/WJFCEXs3zyR9zHz24GM85/i4Ir06dfRqLa+evXWX436u7d7nzFfCRqOXNFJu7

bau+b7r9W27t3b0K32YTs5SJDkcIRsEee+c4xnnk9x+CljJXVpu2l0k7W6rVp6rupNd2c39lSkld

336/zd7rrfTt+JWGgzruCAsHUPycxxyH/nr6evr6jmqWNTSTWttXb1eu/ez06LzMXw3yvmt53971

+/8AyfkxpsfJjw3lGVX2bs5jHUdMHqc89/qc1pHEqbVpO67Llevmld+uv46ysrdLdK1uXvu731tK

62b0tZt9z7Tj1zSEy8xKSycrIspkQnqDK2M9xwTnGDX82TyjDXu3fo/f0le+lk3o+a9kraJs/oN4

xy0bvbW2ktr3s7a7aW31XUmg1rR3LBrqEybTs2SH5+3DHr7Yx0zzis4ZVhk3dxc2ldrd63d20rrr

vqknbc0jXctVfe/vd2l3uuvW29t9Cyl9p7KjC5jAUkJ8/IPBOPbn17HBJ6bwwNKK2b2S9/t00k+r

73+dzR1uZ2lr1aV9r97K+i3d3pfW46e9jkUrbsHd/usBEvXJ5z05PQ5JyevOM62HikkoSTbd9dZb

aXXzt/Ne+ttDng2vP1l966W36dRsjMhEaiRt2AeF9ueufwHQZ61nLDz5U40/dertLduT3S3vLma0

ve711bPdd+ZL5uX6Xfm7soOTMrRmHPeQnO7j1ORwfrjaRz3p08FKfxU0ottyu9Yp395p3vfd6re7

v1l0OfVK2vM7uyd795K6evz6lmOO3hAYpOBs28EZ59cc+gz6nHXFbOjXhvHSKtol102abej66uyu

RUjTd1Z2lpum2933d7tvbqr9GmTXkIkVI0dv3gyQD1Pt14ONxx1GRkcnnqUa3NeNO93vo7v3trX1

1fy5b9nUI027NK7UrJpv3tXvLRa9rt3SXUkijtHOZPlc4LJltueQT1GQT+ffrzHs29W7fjr0td21

fz89TZxmm2tdL3SvdLm1+V35q7V7steTZSMg3/M2TjrnoO+OOTn3z7UoYbmaaWqvJ82ut76u7vzO

y66trZ6ZOtWu0133du6e681f73srZ8tpF9o8uKQCP7mHlCeYenHB45HJXnPHc0VPrHNrhocqtq1T

Se6vqrWTk3e3ZvoZzdOon7rTV9U3aTfZ3k007qW2utnu7FtYTW7lhIzO/DZfnk8EkjGc56nJ/GlT

wlVtOphqfL7zfvQ5tne/Tld9e0euljmn7SnJcvu66crvdtvuk97bpptLV63V1cF3RHXBCOZAMpyC

Bz1HQ/UevNYYrhzI8yfLiMnoS3jPmjGTbtrv7ye2yTW7baTc+3x1K7VaaTu3u3q297tLutdb26lE

6jeOihJrg+UmwYz7c8ZPXnv+NeavDvhBSu8sgpRvZR54uz5pS1ilvdt62d229Xev7UzDS9aWru7u

/nfye71Xm3o2xtcltI1gMs6O3zvIwmXfkdI2xzD04ycdiCc1mvDfh6CtTwnLzXbSrTWvZe9dJarl

SSSutDT+0cbLV1pX85RvZNtee6frdd1cXxFqUuY1Lsc5/ePMc9D/AM9u+eB3PXOKJeHORyjKLwzl

F3TUq1R3TupXbnfV638767lfX8dfmVdt3eqV9r312eyfo13Kr6trXzD7ddbV58uO6l/dx/Tv17Z9

utc0vDPhOrNuVGpGSWqdevZKytopxW17a6p3Vy6OY5lHT2kvPTvfa9nZve73+51F1vxAGyLm9Ctz

vS7l8zkYzkzjn1zn05xXBV8K+DU244NQ09395VdrdUnJa94vmve99bGss1zNO0qk7abtO17tdO/f

ZtX31DrHiSWTa17dupx5P+lXMmehPmEy4wB6dTyOc1P/ABC/g6pJf7O27Ozk6t7e9Ju7qO125TaV

7Xav1N6eZZhf+M9JO692+7Xvbrou60evUktvE3i2xKrBqV3Eso+QrcXEhyB1P7054yT1ycg9qa8M

uF6L/wBnjXouafNKhicTQ5pq7Sao1oq6UlyuXPvr8TT1njsXNN1Ywna3xwjNx1bT1Ttrf5202tor

4s8Tbh52pX8rF4/OH2q4zJjr/wAtc5G7I9CMnuaxl4WZdP462NnfRueNxD5venKN7ylpFN2d+qkn

rJy6IY6ooK1DD2V7NUKair3d1rpra71Wl2TR+JtQyXv3nmBfzIniNzvJEeyQyDzR5g3Hd3PfqTnh

l4PZEpVXNTvUV1L2spScnzOXM5S1bn7zlo27X0bQSzjFQ0SUVFpckYJXSk/dcbpfavbo+a15NnTw

fEvxDb2n2KDV7yO1OcLLMyyIeP3aSGTzYsgfxDIHT1G+G8L8ZDAzweHz/FUqMr8sFOSlSvdRjSqR

fNTjGydua1ktXY83EY7DTxCxVXKcFVq2XNUeGp+9/jSi4ybundxd29erHWHxY8UaLO4g1QSxzbN8

N2ssyHP93dPmLhlxk/NnOORjnwHhdm2X151KHENWUJRtOniI+3V/elGzrVpOD5203T5OdN83NJQc

c8dicvx6j9YyjDXi9J06f1ecW23a9LkVRd1NNXetm+V79l8etfV/9JjsrgLJ1MZRM9QMGU46gDuQ

epJJrgzLgXiek01nGBxSi5NxqZf80lyYmF97JcyTgoybk0L+z8grL/dMTR5laUqOJV21Zq/tIT0v

sk99Lr4jaT47amdxbTtOYH/VyDzIs8HiYk5zzuIBPJHXOa48DwfxLaonQyyvK0lh6v1erTkpOMle

sp15yl7ys5JxenNzvmupnkuRcy5Z5irt3UsRTl916CtdJ20lZtN3TLEPx3vB5clzHaJx89sIpDwc

/wASynP68BT0PDp8K8ZNxlWqZY0m3OjHB1ve+JyUZ/XOZWipfEppSd+STqSSmpk2QOLUIY5c+vP7

elzLTS/7ndO92l71+1724/jlcvu3W+nEsPlPltGWl5yG825IPlf3gc+56nWHCfGEfac0ssnNqXsr

YOtCMJ2mlJuWMqSmleV0rNXTUlzuyWQZHJRtPMbLd/WKPM18qKtz2T1T3uu5ny/HfVi8gQWixplV

kSB5M5685LZwcde/PvwT4V8Q6D5pY7A04rSKp4ST91apODUnFW6Xk2k43lZI6IZFwwl79PHOTld8

2Ipq76pWp2Vr7X7vTrOf2gL23gjjFhY3crrskZVaERF/+e3nMeeuDDyBn5Tmu+jgOLqVONKvkOXZ

vOcJKVdL6q4TejjOE3JtqNruE4RbTt7Oy9pz1eHuH3Vc41cwjeSagqkJdXy+8oJaqzfNzPrpfRtr

8atbWdDLpulSx5k/dLEyiXB4xKbk7j3z0yPzzocP8YKUKuJwOUVoQ1nh4YepCTupWhGr7VqDTSbv

CUOVKKck+ZbSyXh6pzU/rGZUpzaSqqvCfIk037ro8rdn8Lcbtvq2dLp3xysWcJqOhywqcE/ZJ4d5

Y4yIg5EfHvnGOQQa6/qGOal9c4WcuWE5SnhcRBz5/ZuUfZ+0UE2m0rzleLu/e5nI5sTwvl8o8+Dz

y1VpuMcZRqOEm2370qblKSblZS0u9b6adtF8RfA1+kfmajPbs6bmWWE/IPSQRyS42DA+gPBOa+Cz

uWRucaOPq5lgamrcJYPE1JJuWnNOhzxnyyTb5JyafK2qikrckeFeIYylPDQweKjFrllQxEby0fM1

Cqqck5O795ecmt1vWmr+DL3csGr2H0mmWPzDk9N/J5z1znd19fGoZBwVmF6VPHUpzm5Xp4tVMPUq

Shq+VYi1RqNuZPnmpPnld3lKfn4rLOKMNaVbLsZs7eypynyXTerpvlWm7vqrX0HXGk+DLgBJrnSw

zk+XtuoyxA68eYMevXAP3s4IPWuBOEqVksVyTk3y8uaVm21zXTVTEcrdk3orO1nJbso4/iihzyhQ

xrivi5sLU9mno/5Ov/b17X2snXl8GeEpIfNEyQxnrP8AaFVOvBywJbjnHHQHmuifh9kUqftIYzE0

ISTvV+uU5RhzaKUfbRlzNaytK0fdkm90b0+KOJIVPZ8kqs93RVCbk7PV8qdr73vre+7I7b4f+H4X

86HUFkyvyhJo3THUglPqeQOp6AHnmj4V0qqvLO5Yin7s0oSw8bq9nCcownJttct48rd9L7lV+NM5

rRVOphHBxbbcoVYS3laylLS2z6tJ3d1YvjwhpwYhLxhuPH7/AOZvw2EnGPf/AByqeEeFm5RjjatK

3NyP21Go5PSyalRtFrsr8101K12uN8R4vlvLDLZc/wC6lyx6tt83d9W7f9vNqaPw+bRn8q6uMjPy

uxIJyCwxhjyO+cg5ZjXLPwzznAtvD5/WTjpaSp1IunfnqQSc/dk7Qjzxive+zayWM84WIsqtCnr2

SvfXW7sktHo73va7aZow2V7HwZXY4OBt5I/IcAZ6HOTxxxXZhOHM7waftcyeImlJxtQjSSfvyuoL

nmlKLtNyqTfN76sm0+KrisNVtanyu7bvtf7rW/z6vd0kbDhs5/iPUk/Xpz25/wAK569DGUE7zakp

Ozceq5ry7e9728r669ETGafvRd4rXe+99+t9dd2r636SLI4Yg8/NnoORnJ456Dv+JzTp4vMIOUZ1

b3d4r2cLt397Vt2T1XM1d2vdtNqWk16r1e/VvfS+vcFdmU5jJ5Hz8Z9ODg9uvUA8mujDVp1ac4rB

+/aTcvaK8Vd2lrdXla6XN7kuZPmS1Glp7ySerXXZ6at7tPzd++remeSue/rnjr0yOcHqTnknrSjR

tO7w1tZNXlto95drdU3e+t7kyV91e+/mnd3b79d9/PUYc7gw+UnOcj8M9+p56/MevvdSpXU1OMFS

Uk3dpJe7pe97uTcXK93dvmXlV2007vl83p+KV1vtdJ3QwsSwJc8Z4JJzn3GPqDg465zXHUxWPU1/

tM42b5ox5deZeW1t9Hba+2ha11Zed0pffe5YRyW5B5yCSTyRuI+m7AyT0ycAniu2niataXvUJR2j

LmlOV9ZtSvvHVuXxWjeNo80bPGpBWbukl5LRXt0/4f8AVhniZsCTcc5fJ5yeTz9c9T2yehNYyxWH

dR3nG/M3O821duUn72qja0r3lJxirys7sp0qkU3KPLe3LpaPX5X1v636WtzXih7OfTbiENJ9qADw

BXJ2uhA3P/Dgqxzkg5yfSvnuI8Vw/jMvxMHipxxeEqUqlOjCq6ylWfNCMasFKS5aylOMXL3otyqt

y5Gl72QLFUcbSrOMPq7vGq5QspQlFrlpt2vr3e2iblt4Lc6/9t8SeHtL1K2uYhqd0+nw3UkqJa5h

hluS0sechhHG6xnH3VOQOMfLYfA1q+X1PZYyjy4KnShCNTnvQp4nFKnd1HdRpQqYhSqPZQUVtBH6

5HLqeXZTmOJwVWlVlSpvEOlTpSlWUnFyUFVbUlFqMpuybbV+7Xzd+1r8d7P4L2HgfxPLZ6fq9rpn

iqW3lsLNU+2X3/En1KHPngyRxxmOQQzpEIZ7j7RbgEwbs/rXhBwTieN8bmOTcmGwk8PlUKkcRFc+

DrulmeDlKWMhCpbETqywqlCtKKUqFOdSV5zpzfFh6csBgalZ/WlVx04+5VnJOlenOb9ippSjZ1H7

0+dqUmoy5vap/LX7Gvxl8a6r408Z/EK7+Fdzr0XjHXG/s7xHFabLHQlW7uS1hbS3CK6XMkbtFPND

OLicwBp4FGa/avFDIcn4Uy7Jsvw2e5e62Q5fTo4jA5i6tapXrVY0ayxi9hUjSpVpww1b6v7WnJUo

VaroTnGNSE/VjlizvLKmHxGJr4WFScq9WpQnTpc0Vzp06rqXcqC9rCVaHNpOFNySaUo/snbeI/E2

u3Vqk0Frp8cYUzwQvJKkagchpJc+a4Oc7gckjjPFfyhm3GWe5/jaNLKKssJKN1g8NglKNJq3vVsW

8TOv7SEVJtuSUb8qVOdTkb/NMRk2RZRhcQ6dTEY2pUk1Rq1FBSlPa8Y0+Xkhd35tLwcX/i7aC+ty

AgkEh+6XT7pc8naTjPfAyQc/hX3CxGGzKjhp4jELFV4R/eSozVOMqtoqTUIzUZa80muao0/icmnE

+UrYKteU37j3UZ61OTda2bab6p726PmLmVJ3b2x/uk59SeOn+fUHZwwTs3iPdV7/ABt30tLZrVSk

u/TrK/NZ2tyq+jvzR0vvbVJu/bXq7XDMfdyf+Anr+Xrzz3qYxwcFripTSv7vspwlzWfq/id3zqze

71uS+e+3fdpv563/AFfmCkeYRt4ONw45B56eh6/z9adCtQjUkvZLkd4yS5ZOSd1flldW1erWnM1/

Mm3fl+LVPfq9dbvX0vL/ADHMMnfjOO/UYzxnHqSevrXtRUar53R5uW953Tv8bjbW616SSd79btK6

V03a/TXRvfV/LUQf3WU468njnr0PXr7tk+lTKUIWU6j62sp7S1d+ml3fVtq+6Q97tPdW03fk21ft

6Wv5iGTaQvUHg8/3jjgcHnn24PPNc068YS5HJT5n0bjeLers2pLs38N7662GottvVd9tdbtve+/q

NIyxwxBYnoWwx5x+WDj0xtHOKxqUIVJf7NWUHUjdR+GLtKUbS+zJc0XK6Tt09+6YpWj0drrXl72t

sk9999U29ZEoPXLEHOBkkcn8/wCXHrW1CajaFarOTV4pVJTldybUuZNv3tLXm01u+5LXWKWlndav

r5PT3u+za2erl6HP3e2fxz/Ot6cbJysuWT916aq783f4rX+QPdJu/fXrby2em297jg4XONuT6D8e

2f8AP41tDFRi3K8ZNq2sGn96i9L/AOfe8SpuSSu7J/zNt+erSvv63taw7OMj1/8A10ubrf4vP4vt

fPa/yuO0JSVtHCT0SS2118ub8ea29xCfU8npn/PPNOScbc2je1+utu/fpv8AeJJycnze7otFbzXT

4U29b37scjbOgHHTjn8+f881Uaji3J2e7u9LaNd+z172vp0yqdHaSS0u00nvr53136JdhrM598c5

P/68k+5/rVurOV1GK6uXPqndt2763trba3UahGycna9tr9Uvx6/etdAUkkZ+8evQ55689Sc8+/pV

Sbmmp/G2kr3dm5XettmtX+thSVtYfC79VrdO613623d33aHFhggDnk5J59/z7/5zajDl+B3evvL3

t92731tfTvtqS3JtNvW61utOvTbe/TW99UwU4OcZqlCCbaitXfVN/wDpV/8Ag/ITk3K7ab9E192q

/wCD5jiQdmB/TufTOeeayq8sXH3L9eya/l2krX1at1fWTY1FWk+dK/R9Vffq1teyu/vu2KAW5Ue5

b2z3/ofp3qnTpKV5QV+7u27P7Wr0vL7Vt/UOeVlaUvle2u21t/n1dyTZk9Tk8468n+ffFa06b1bV

nNycru/WXnrvZ/iJtu3ZPR2tv6ddL7731e4FM9/0ArRU46uNvPlS/T1/Ekb5IOW6+4//AF/5z71P

sF/M/uNVVnsreSS8yPy2yB06kt1/z9M9+fU8/sfejdarabve3+Ld763bv1vuae1jaT7v4f8Ah7/N

/d5S+T6H3wv15zjI7fqOtaKHm9/6/wCHuZOq3fRO61b1fXW45UIOWHIJGM/598/WoowV1U3393zb

evn1379bkOSd3Fu0td9/687slPzk4GBjp1xgdOnfH6n3rWpOyc7X20vvfT59yW7K/wB2u9/Pr3/E

cu5ed3yn0zz+H1PNS30s1L1+b1vrp3/Uh2btb3vk3rvrfW6vvuXVaQFCecnnPU/j157n344q4uSt

Jv3r6u+zffffra93fR3OR21t8v19fK/TqNccgE/e554z35449T/Xt0Tw9nG9S/M73S8k1dvXd672

13ZrCL96d1eOuqb832eq/PfchYFd3P3M/r6fU9f61hOMoS5JN+7bzve1u8Xzfat3XQ1unyprWaW3

93Wz+d9v+CMUsp3MpIU8+mSenoepPX9eank2bjr63tfffu9PPcJxi7paOWqbbTa3u03e72a1a31s

SKxfB27i3tnP0/x59azlzcySi5SlfXlerWqs3o+z1b6O70M3FRuufZa+V1fW71v5W8tWDkgjK7du

eoOOvUjAP/68UTqSW9GUeXXeWtnd9Lu1tbd1dNhFL3tebmtfXXrd3/HXbre1xPM2gZXP97t69MdO

3eumGJ0cVdrXnsrStr1cXtvbd+9pfU0acpNqbVtla1nddWn/AJ38hk8wQeYV3JyTjPPX+v3eT1yT

zgzimqteF4xUEt23zWfp1UpWWuid5dmoU3OfInrotLbO23rfV28rd8TUdXFmu+2tXkxJuz5WQ2f7

iAfzKkZ3ckk15PE2df2Bh44ihhqlVylFS9nBStFq7ajKyUIuUnzOXup8yi3bl9jB5b9aly18RCne

Oj57NP8AvS11S3S+7SxWtPGFjJGftTPA4PzBomJHJ7ruGPf8jXm4LxJ4arYdLF4nE4WvUjG6nha1

VqUbyacqEK0J3k01OUlN3V7O6fRiOHMVCpehyVk0+W1WK5knpe6Xq2tLq++rZa+L9HlnlU3LqFU8

upG489yQMn8S2fWowvF3DdbEVJPM62HXK5QliKVelGb1taVSCV1eLcW4ybT5VKPNIMTwzmdKnGTo

3lJvaV7ertd7O3XTpuQp470WJpVuEuRBlohIoJCZYnzYlXLAEnPIGMjnpi8s8RcmoY/E4DHfW1h5

e1g8ypUVKEleWsKMJSrrn5pWnyNu3NeWnNs+Ec1qKlOk6DqtQq8jlrJveNR6RTvfm1vpZX5Wef6n

qXgi+vo5xaX0rNIwlcbkAX1IMv7zrzzk5LEnPPhZhifDeONnVwmEzWrSq1HVqTXtYU+efM3UdKti

Y1L87TajD35JuSk5Sk/s8vwPFeFwtSi8VhKaUbwjdTtKTcrNqlLlV21bRnXx+BvDt5As8MxKTiMx

yjLbBx2PUdssfp3z60eBeFsZhadTAZ5UbxFp0p03UqcsZN2a55ckl70bualom17ysfMz4tzvC1nT

q01GVJz542inLV91dtay0ve7bTsP/wCFc2KZaO7EhXPkiRCrADj5jkYOcHgAfXiuCr4R4upzvD8Q

Qp0525FVwPPKS96/NKNendu6Xwxtq9eb3V/rvi2+WdBr/n5afNa77OLTtru9d7rRmRqXwnTVU33G

oqzIPmdo5WYJyY/uTIcJ34Gcn0IPdhPCnOYv2lXiGjBKKXv4GrPkhHR2dTEt8vVRjdRXw6O69DB+

IbwcnCngZKE38MJxTlJ35ndwk/fs3311SbPPL/4HXAx5NxE6EOucuA2Tn/lqWI7/AHvcj5uv0tPK

+NMow9LDZTmlCvGDlFKWDo0YVkrLWXLVlD2cbJ++3OXvNvVnsf67ZDjeaWLwNWNTR3VRaOV23ZNx

lda20ve1lrfHHwevIvOh+zqxZB/pCuc5PoS4BOSeh6ZyOOd6nEHiS/Z4Z4Og5yb9tiPawjT5E4rS

LkpOTi3y3qWfJeThGaidsOI+GlCHJCUG1bla9972f8N6Wad7Xe15bqvJ8FBDY3UtxJczSmL9xbox

eTzGlyHGMkknGDkHoDy1erLPc64dwtTH161SpDk554enH2tarU95vlXxXcna2tpN3d98lneS4jGU

aMKbVOU7Sr1JJQgnGTdvdXvLZptrdttvThrf4ZaqLgLPp90IQ0ivKIXcmM5xmLyeucE84GTnPJqs

P454pQVOeTY2nCyUqqhWm4q007wdKyejs1J80+aTSacl7c4cPOPtFmNGc2rqneEbt625vauPXWVn

6s27D4PW948016t5DHAcsvkOjshJ+aMuWHmZAG3yf+BAdd8B4vU8xrYn29LEUfYfHGVCoueEpPld

OXLo5K+kqaqJe84uzR52KxWV4X2cMNUjWlWuk41qaUXdL3+VTTjrdvm1ta3VcvefCtp9TxZ3yWkE

bj5bhATNEScxZjIEUoLZ3dCCMZHFe9kvidSxuLlQ9rShGM5LmqVU5uPNKyteLjUSV3DlfKmtEpcx

21MLg3SjVXPzzteEU5ShLmtKXM+VuN3pJK93fqcpqvwt160aaWKeGZVbyoYYjJG8x6/MOfKiODxg

Hjk96/QY8WYdWnKpSsmotuac3ZSvrq+X3t7rmk29bM5P7LpVk/ZTTb99XbTjB6tXTtzL7STm+ul0

ea3nhbWbBna4imjtUkEUj5HPfr64Jz3Gc8E5r6bA8SZZVcY/WKbu7W50lu3b4ru+qd+lrLV35/8A

V7GxbahKSbstVs29d9b69ut00rGd/YNwS8+4/fJGEBkOemWPB453dSexPNejXz3LlpCtByd+aMZ8

95d2+bRPRau7136dH9g4tXfs2ktU73Xnf3NXe+zv57Xp3Wl/ZgqtKG527Nn+r3Yxz36447nvg57c

Di6c2pRnBtqTWqt9p2dnbr3u7aS3vEsDUg+Rx95b3um37197LTXfz63tz8lvbLdbZZdyjDgeXjrz

jPXrk/1rsxKi/e5k29Vre/wrfmaat7yduu7N6dDlV9b+V9b381tfzRq2+n6dLJC88m2PO13TJYxj

ocgc559PXnBpVOVOFmkne+sZa6Svqmtea929VZo7KdOMm0nZXfTRt819X59dbre5ieIn0ozo+mxO

sCZi/fP+8l8vGZTn1HGep7n178NOHRq3e9nZc729d+u6PGzKk+a6Unqtlo3re1l5a+d+5zrZdl+b

YqKR3P8APPrXZOVk0n7z9H17PTvv5nlRjzPa66/1/X4lhbqQIo82Nf4I/fA6dcnzfXOf64uTesm3

0utW+Z/3dfPyvbU6qcdLRtzN33d9/tXfnb7i7Dc3EyPGHCq2fLymJP3ecjscH3/DBFYSjZW5l7q1

tdcuml1ftfV+u7udismko2T02dvK7fxWfy79DQa/1OVlQhJJm+WLy4P9Z05ORjqcE4BOec8V4eJx

EIXu4qV9W2tW3q7q+jt8k+bfmZ9HhMLieXnpU53VrySbbd9bNO99W+210tW7h0jVZVBeF043jOd5

5Jz3756nHAGa5pV8JXWvLU72Sl5N669vu27ehTpZhTbleUdV/Mujt8XlurXet+t5YreS0iS3KzRy

KOiSKN/XnkA8deOTk9s1HssBHalFNSs3Hf4pKS+dt7u6ktNTt58dL/l5J/J+XXn/AOHEE91E26Mz

Ptjz+8eX92eMd8kEnOOuBn6aRoYSqrqKastFpa75tV33117drYVMVVe9eo276+9La7/m0667NXbs

tCv9vntX3zyzGPIc+YBInXOzp/Xg9RV/VMNC16UWlbRrnXvd9++t9utnc5HmNaLb9vLRtv4ltZvW

/bd3aaukyyPFrQCKRIkJ/eIP3YklOOspBxjk9D0JBPfLeV0Um4QSvfWKvpytp9buT11bXNtZ2L/t

2u9JuUlsua+u/wAUrp+9r7y5b6u+17lv4wupXRpFtfIizJIs0EYkOB/qvNBzD3z144Oe2lLK6rla

NRyUXfl01876q226/M0Wd05XU46uy5rJt3bunzLzfT9b0JfEZjmJaSN7d3LhUix/5FHB7kc853E5

yKMRhlN2cbyWl9bN8ttWrNpP56W1Esw5ZKK1u1Ldaa30Wy0emt3uadv4l0vavmuFV+X34z8mDnJ7

jJHUcZ7njxcfh4U4rTRuXNvsnaTfM387tuz3V239RgMSnFNyi7xs+aWttNb3k3ffZ3XfQ6aPVPD8

7Ryy3kDYSP8AdnP7vr/rY/mznIweehJ9a4pKlUa5pQlrduVnp5q6b3d10WqbZuqmHV/e05nsk9Lu

2uzfn1t56WZtV0RYXFvcWbb32YVSnTrydv079OmCSJdOlb7Dcr7JuS6y6u+2vNq0m76CdegnrJLv

e3N662/PfqWLfVrO5ngjkvIWXzP3jmQfcjh7nqMH8s47V58sMnZtNrma1b0s3/es9Lt9rW7m8MRe

L5ZJpu++qV7qzb6brV7ve5HdyaRZu1zbzQ72J5P7w9OSOfpgnPucdYWApVL2ik7byi3vzKLvdtrd

306K1r3ccbUjJv2nfR+t323u7+91aWpmm90O+CvfXpj8vhxHITH1JOerebxzzkDGe5rDEZLUunO3

LFXbskr3aT+HdpdOt7Xu798M0wtb/l9d9Pek3zNSX3N7PW6el9b2o9Q8AwBXFxc3BbCs1rdzGSPP

J+/3BJ4JOeSW9eb6jh4PWFVvmSfKotqNk+qe7b11srvykTxahfkxFBPXl51Ulf15ZrXRa66JK2rZ

Hqt3oc8Kx6ZLfm1lQK/m3BE0b9W/1ZLRYGMnnv1Oc+rQy3LVHljCUY7LmklJP3k1Jp2Tbut+mjd1

fzK+NquN51lzSvzcilytXfLa95PfW66dtVyv2G1aX/XTO7fx+a+Iv89eck459a2qYPAU2/3cItK1

3ey2e1tbOzbTvq1eysedGvUk01XvrdfFq5J6r3ndO977vdvXXYtNDt4i8qasLSeQD5/MkjkkGcZx

xj245J/GqWDy9Ra5IKb0do2b1butHq1o33e+jOmnXxin703yvWV73no7et5Prrq3ub/9iPKFiuNU

h/dJ8vnTyyZ6c+Uf1PPXn1HHRw2Gp1KilGKs/cb+Gzcm7qzjF8zaav8ADL3raI660qk4+83eSd29

b+Se78023qlZIoz6PO48qG5SJOrs8vl5+v8APGcfXv1+3qKzioKNv4jcPcd56O+qvHld0naUnzJ2

s/Cr4Sq7v3nq7bvf3mut1823t1ZFaeHL64ci2kE7J1kiV3/wAPPY55PNL+1ZqSXLF2vdxjdaNbcs

l1+Ls5L7RNPKp8vPKTg3pzVHZa8zXxaJdnqt+uhvt8P/ABE9vMJYiI3Tl3mVHz/uCaaT1JbPB9a7

VioqLlOOm7b0k0tfdipNtv8A7evur3scc8DzSUI4mi5O6Vm5JXvZOduVebbX+fOt4N1TP2XzVYMm

wwklw5BOQT5vsc88En61pDM8KpcvNdytolKXOtWr2et2+/V63NP9W8XNOcnC1rSl7WFldW6tLftq

9r734W98L+N9L8SR6HBaS3D3cSy2kIZSbiOQ/MY45Zsfuek+T05zg10zzmhQrxoqjJzqQU4QslUk

nd80YuV3yW13+JNK9zgfDVapTlX9vBUYualUU4eyg4u0v3nNy6afE1zc0XdWV+ttvCWv+TvvIPs0

6f6yNmEhJjOZZYgPTrjOexPQnKpxRh6UfgnFrmbVr6RdnJe6m0pcmtvhlrZ6uocG1K1n7aMk3HTm

g97cqb5tW+Z8umsleN7MdpvhbWLoySwyReRjyoyr+U5kjzF+8BDHnr1LDng9KKfEeGrxc4K6bk+d

y0undp813JtPm+K/e91boq8FThL95U9krN2lpo7a3e9+r2butPeb6C28BazeOYzMkbbdxdgxMhj5

z9eMgDPGc84pPPYNtQg73fRNOOt5ay/uyt0V+trrGXCtPCx5p4qEYXS+Fyab1TfLe+vRu2q31RoJ

8NdXgkdUn+0bkyPKChM54/jUjOMk9D6jg03nkfeSpuT2UopNXd9dJtPXz9E9xvIsG4Nyx1OOjTvS

mnd7NpX7+f43Kv8AwrfxHLnZaykLuw6wR7F/DzSM8dwSPfkjkfFFP3l7KpdfFeDUd9+bma3fXXTa

9zF5DgqcnJ47CRctlzb76qLbet0vK91dXEf4WeLPKLmxnZU+aOMQqpkT1LY75J5yCCBk/erKfEtS

KlKWGqqN3K3InJR3aV5Xm9U9Et7X6vGWU5e5ezWZYRybS/jx0b6PmSS2b1u1o3zXdqTfDfxXEmJN

KuQGxnl375ycdSCckEk/zrOPF0IxcqlCrG97XpyaW2l1y3fvfdbXVsdLIcM7xWPwkmnpfEUoW72b

lqm7/PTW2s0XgfxOHcw2N+5C4fbbAGRP+/447kAqSDis1xVSqScOSrJNPmSpzba17xXTez0Vve90

0fDtOlZzxeCSlJ6yxVFa31bXOr6u95J63Lf/AAhPi3YmzSb6V1k3H91JJyMjJBbdg4OcfhUvO6VR

8/ssRLmd7+xm22rdb3063u+50Ry+nTeuPwSXnicPFatN+9zXbfq+tkxZPBnilJGc6PqKNjdGfIMn

T/plu5zj6jg9DRPN8PGSjKnWc9Ev3E3fm12ve3326edxynB25oY7BPq/9so2u3JvXnV079H3V9ES

f8IJ4taQmTTrsAkycRyId365Hf1z61rS4hpwTi6VZqz92WGn563s3u73uthSwGH/AOgzBW6cuLoy

d735n7z30ey822zf0vwN4xe4SNtNu/LXrIoHIbPzDOW49DnlumRuHDi89jK7hhKt9LWglvzPnlJt

y93S8rfFb4lcing8roLnxed4ZcrbfvKTst1e75t+rje+6Wh6LZ/D7XkeOUWslwJHymVZ48eX3BJM

0mM9SPm553Zr5avjsTKopwc/fleLUaji0ozd2uX3m7LR3Wl0tiv7T4bpXjUxPvRu3zSipXvb3tJc

qctpPe+l3q23HgbxBLdCSERwBn2F0fZ5Rb/lqNmPK6+hLZxnGK5cdi8xxEHFctODjy+1UrcvxRUl

yqTXKrbtaznro1P1MNxFkVCErSnP3W+R004yva6Sn8d311WurcW2d5pVl4m0xnjvfEMd6jLHEEQO

06oFOUeSQ/vUiPBOAQfcLXh055vTr1HiszpYrnslaLU6ScZaSlJtVIw920mr/wARt25EvmcxxWR4

/llQyaphZXlK7lFU6k+bWUacLclSbb69k0leRjX3h7xUblr3w/vMkxeBprdWx5b8+WNm0+YM5POO

ckjqeHFYPOKlT2+WckZVeajUrR52lTlzWVNWt7ROOzlFXurs9TD51w66Cwuc8qhTUa8aNeUPjgvj

9+Tbg9lfWzW7bOdvfhn8QtRnW4uY9RuH/dl/tEl4B+7JP7vzJiBnJPTkk+oJ83E5BnOIrRq1nWrz

5otqdTESWkVBuF6vMrrm1Tj8T0T5m/ZwvHXBmCpypUKuCox963sIYfmfPb47QWzvpeV93pdnrul/

By8n01dS8T+KoLNoIlkljJ3eTEqAJHiS5VItg/dy/vvLbrkEGu/HcAwx8KtTMs6hRlSpupKWrp4e